The Ford Foundation’s Footprint

Text by Tom Avermaete

India was moving to formulate programs to really carry out the Gandhian concept: the Gandhian philosophy of village and rural development. So, when [US ambassador] Bowles came along, looking at India in the concept of the Truman Point IV, he… jumped on this idea of U.S. aid, tied to community development, and this got a very great response in India, because it was not a U.S. imposed program. The U.S. was not dangling large sums of money in front of India to try and influence her to buy a change of policy, but of helping India carry out its own programs and its own commitments to the people. … This big program was launched on Gandhi’s birthday, on October 2, 1952, with national enthusiasm, and continued through the next five years.

— Douglas Ensminger, from an interview released in 1976

The Ford Foundation was one of the largest US private foundations in urban affairs during the post–World War II period, followed by the Rockefeller and the Carnegie foundations. Established in the 1930s by Henry Ford himself, the Foundation extended its activities beyond US borders to developing countries in the 1950s.1 Economic development and aid to the world’s poor countries was seen as a critical condition for world peace at a time when memories of World War II were fresh and the Cold War was menacing. The Foundation’s spending figures demonstrate its strong international commitment: 2 out of 5 billion USD spent over the period 1951–1981 went into international activities, of which three quarters were directed to developing countries in a program called Overseas Development.

The ideology of the era held that proper development assistance was to be funnelled, top-down, through local (newly established) governments. National planning was the correct and forward-looking way for nations to make progress and improve the welfare of their citizens. Urban planning was an integral part of national planning. With good connections to academic and other settings from which to draw experts, the Foundation was well placed to facilitate a supply of economic advisers and planners to supplement the planning teams developing countries had been able to recruit among their own people.

In 1952, the Foundation’s first, soon typical, overseas project was in a rural setting in India. The office in New Delhi was the first the Foundation opened outside the US.2 On a direct invitation from Nehru, the Foundation was asked to make a contribution in India towards the advancement of human welfare. This was soon followed by the Ford Foundation’s involvement in Pakistan’s city planning (1954 onwards, starting with the Greater Karachi development program) through the Harvard Development Advisory Group, as well as major urban planning and renewal for Calcutta—overseen by Ford’s representative in India, Douglas Ensminger (from 1952 to 1965).

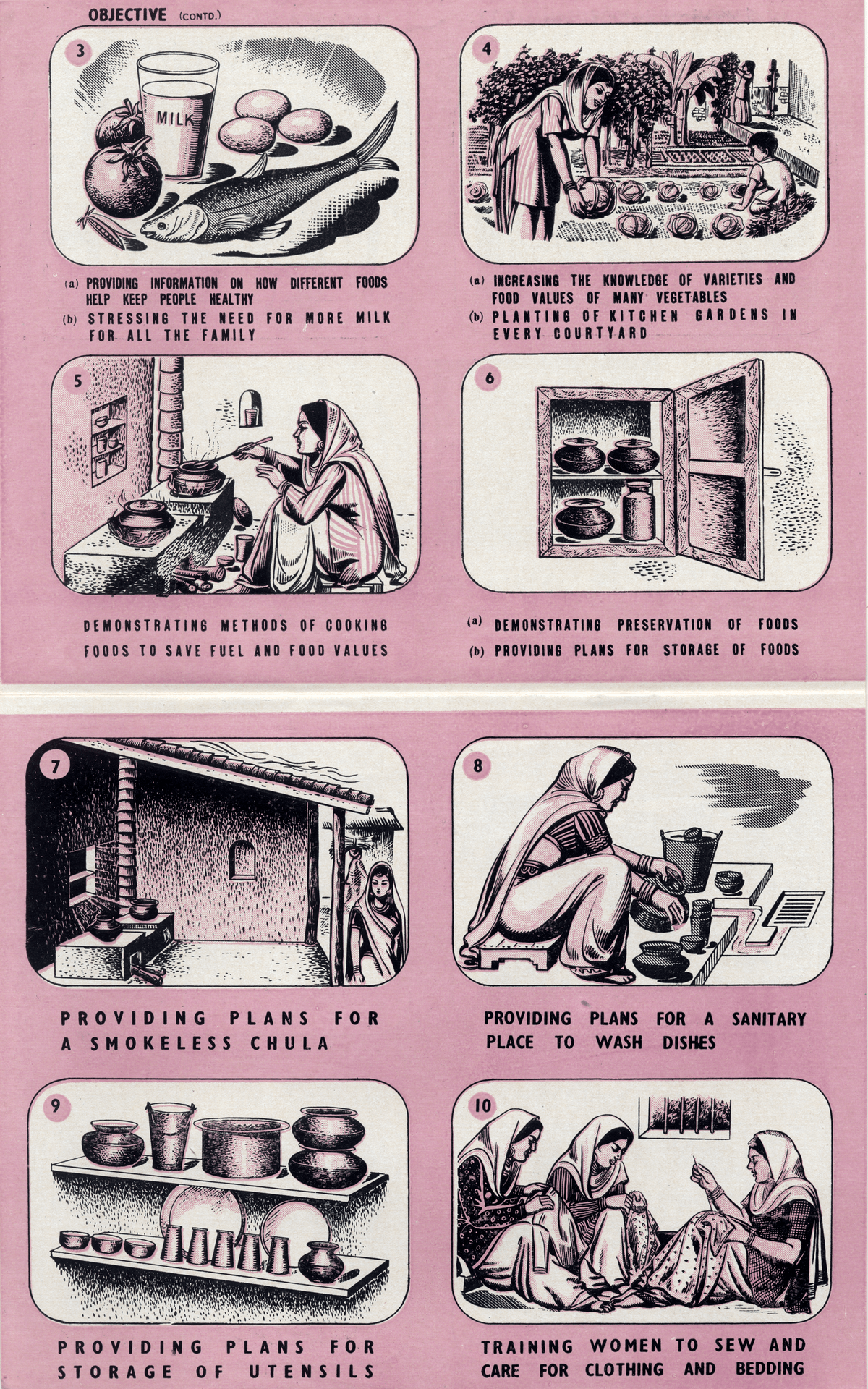

Under Ensminger’s leadership, the Ford Foundation acquired extraordinary power over the Indian government’s development plans, notably financing and administering village-level worker training schools.

-

For a general account of the Ford Foundation and its beginnings: Francis X. Sutton, “The Ford Foundation: The Early Years,” Daedalus 116, no. 1 (1987): 41–91 and Warren Weaver, U.S. Philanthropic Foundations—Their History, Structure, Management and Record (New York: Harper and Row, 1967). ↩

-

Sutton links Ford’s rural bias and Cold War competition in Francis X. Sutton, “The Ford Foundation’s Urban Programs Overseas: Changes and Continuities” (lecture, Rockefeller Archive Center, New York, 25–26 September 2000). Farhan Sirajul Karim writes extensively on a significant episode which illustrates the Ford Foundation’s role within the Indian internal debate on the impact of capitalism and the free market in industrial development. The Foundation was fully involved in sponsoring the MoMA exhibition entitled Design Today in America and Europe, which travelled to nine Indian cities between 1959 and 1961. The exhibition prompted a wide debate on the impact of mass-produced objects of Gandhian material culture. Farhan Sirajul Karim, “Modernity Transfers: the MoMA and postcolonial India,” in Third World Modernism: Architecture, Development and Identity, ed. Duanfang Lu (London and New York: Routledge, 2011), 189–210. ↩

A selection of leaflets like this one was included in our exhibition How architects, experts, politicians, international agencies and citizens negotiate modern planning: Casablanca Chandigarh, held in 2013 and 2014, and in the accompanying publication, Casablanca Chandigarh: A Report on Modernization. This text is excerpted from that publication. Tom Avermaete is a Professor of Architecture at the TU Delft.