The Work of Counter-shot

Text by Samaneh Moafi

By the early 1970s, Cold War fever was at its peak in Iran. The monarchy hosted some 6000 American military advisors while Soviet military aircraft were consistently entering Iranian airspace to spy.1 The Shah of Iran was allowed to purchase each and every American-produced weapon system he desired, but very few at the time could match the high speeds and altitudes reached by the Soviet aircraft.2 Among the few competitors was a new supersonic, twin-engine, two-seat, twin-tail fighter jet produced by American manufacturer the Grumman Aerospace Corporation. The aircraft was named the F-14 jet, or the Tomcat, and in 1974 the Iranian monarchy purchased eighty of them.

Grumman was not only contracted to produce the jets but also to help design and construct a new airbase accommodating the necessary warehouses, runways, and control rooms. According to the contract, the airbase was to be located in Esfahan, a geographically central city that was regularly targeted by the Soviet spy aircraft and that offered equal access to all of Iran’s territorial borders. Amid the construction of this airbase and to inform the American public about its work, Grumman produced a promotional film called The Grumman Challenge, in 1976. The visual and linguistic rhetoric of the film attests to the strategic nature of the project: “Iran, 7000 miles from the United States, sits across roads of a different and differing nations. To her east the Indian subcontinent. To her west the Arab world. To her north the Soviet Union. To her south the Persian Gulf and the Indian ocean—these warm waters Russia has coveted since the days of the Tsar.”3 Indeed, the implication of the film is that by supplying the Imperial Iranian Army with American weapons, the Grumman Aerospace Corporation could help secure Iran as an ally for the United States in the context of the Cold War.

-

Ervand Abrahamian provides an account of the expansive resistance against the American influence in Iran in the 1970s, including the bombing in response to Robert Nixon’s visit in 1972. With reference to a series of leaflets produced by the Mojahedin entitled “Military communique,” he explains that “the United States was flooding Iran with over 6000 military advisors to stamp out revolutionary movements in such places as Vietnam, Palestine, and Oman.” Ervand Abrahamian, The Iranian Mojahedin (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1989), 140. ↩

-

The Soviet MiG-25 aircraft were equipped with powerful spy cameras. They were designed to fly at high altitude with a speed three times faster than sound to take aerial photographs of military sites and strategic locations. Tomcat Fights, episode 1 of 6, “First Kills,” directed by Mohammad Shakibinia, aired 2014 on Iran National Channel 1 TV, 36:58 min. http://www.filimo.com/w/ZzIAI. ↩

-

The Grumman Challenge (United States: Grumman Aerospace Corporation, 1976), promotional film, 19:53 min. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=enaUs3MZX6Q. ↩

But the scope of the project exceeded the military concerns of the Cold War. F-14 jets were built with cutting-edge technology and the Iranian Imperial Air Force was not capable of operating them without prior training. Grumman’s mission therefore included a pedagogical program according to which a small group of four Iranian pilots were sent abroad and, in turn, an expansive team of American employees was brought to Iran.1 The exchange was disproportional and, what’s more, Grumman encouraged its team members to bring their wives and children and built an entire new town to settle them, autonomous from the existing fabric of Esfahan.2 Construction began on the new town of Khaneh Esfahan—which translates to “the Esfahan home”—in 1975 and the Grumman families moved in shortly after, even as building continued. This extensive housing strategy was one that would appeal to an emigrant community more than it would to a team of technicians on a business trip.

Mirroring its parallel investment of military weapon systems and new-town designs, Grumman’s promotional film has two parts: the first is dedicated to the Tomcats and the latter to the new American-style homes. Accordingly, the first part is filmed against the backdrop of the skies of Esfahan and the second part against the backdrop of the city’s barren outskirts. In cinematography, a shot consists of two points in a hierarchical relation to one another: the point of view of the camera and the viewed point of the subject. Seen from a position high in the skies, the new town appears in Grumman’s promotional film as an outpost in a desert; and conversely, seen from a camera positioned on the ground, the fighter jets appear as pioneers of Esfahan’s airspace. The latter, known as a “hero” shot, is the counter to the former, the “aerial” shot. Extending the logic of countering to the scale of the body, the technique of the close-up shot is used to depict, in the first part of the film, the aviators in control rooms and, in the second part, an aviator’s wife preparing a meal in a kitchen. As a whole, the film is therefore a composition of shots and counter-shots, both inhabiting the same structure.3 The juxtapositions between these shots reveals the inherent work of Grumman’s mission—the dual occupation of the sky and the ground—and provides clues to the two types of capital that the mission was acquiring from Iran.

-

For accounts from the Iranian pilots who were sent abroad for training, see: The Tomcat Battles (Mohammad Shakibinia, 2017), Documentary series, episode 1, 37 min. ↩

-

At the time, the master plan of Esfahan, known as the Organic master plan, followed the logic of the New Town movement and only allowed expansion through the building of satellite towns away from the traditional fabric of the city. Organic Consultants, Plan d’Aménagement de la ville d’Ispahan Phase 1, 1967. Archive of the National Library of Iran. On the weaponization of new towns for urban development in the context of Esfahan during the Cold War see: Samaneh Moafi, “Architecture and the Making of a Gendered Working Class during the Cold War,” The Funambulist, no 10: Architecture & Colonialism (March-April, 2017): 34–39. ↩

-

The title of this essay echoes Walter Benjamin’s critique on the mechanical reproduction of a work of art. Walter Benjamin, The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction (London: Penguin, 2008). ↩

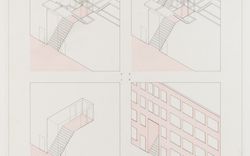

Stills from The Grumman Challenge (United States: Grumman Aerospace Corporation, 1976), promotional film, 19:53 min.

The film’s narrator explains that in addition to money, Iran had to invest her “human capital.” The term refers to the personal attitudes, talents, and habits of a society; those that, in retrospect, inform the manner in which labour is performed and the economy is structured.1 For a state to invest its human capital is to subject the elemental acts of living of its population to a pedagogical reform. The narrator adds that the construction of the Khaneh Esfahan is the means to help the foreign land of Iran “[take] on the colouration of American suburbia.” This colouration was thought to be achieved with the domestic lawn, an icon of the American way of life.2 Indeed, the new town was designed to resemble a green horizontal facade within a desert landscape. Given that the regional climate was hot and dry, and the local piped water system was unreliable, maintaining velvety lawns demanded excessive care and improvised irrigation techniques.3 In addition, the walls that separated the lawns from one another were low, which affected the way neighbouring units related to one another. As one of the most common features of the houses, the lawns were used as a stage for the performance of familial activities, from minigolf to barbeques. Given that the partition walls were low, neighbours would have been in each other’s company and formed tight-knit relations.4

-

The concept of human capital goes back at least to Adam Smith: “The acquisition of … talents during … education, study, or apprenticeship, costs a real expense, which is capital in [a] person. Those talents [are] part of his fortune [and] likewise that of society.” See Adam Smith, The Wealth of Nations (London: Oxford University Press, 1976), 282. ↩

-

Beatriz Colomina draws a parallel between the strategic role of aerial photography in military inspections and the bombings of World War II and the idea of American lawn as the home front. She argues that the lawns of the suburban houses of Long Island were the domestic frontiers for the veterans of World War II. After the War, gardening became a common activity to promote psychological healing within the American army and navy. But, in addition to playing a therapeutic role, lawns were also the setting for a violent form of warfare as spray guns, poisons, and traps were launched against insects of all sorts. Keeping the lawn tidy was advertised in American media as “a national duty performed for the morale of both those at home and in the armed forces.” Colomina argues that wherever the American soldier was he would dream of these velvety lawns: “he wants to come home to them, keep them growing their best awaiting that day.” For more on the American lawn see Beatriz Colomina, “The Lawn at War: 1941–1961.” in The American Lawn, ed. Georges Teyssot (New York; Montréal: Princeton Architectural Press and the Canadian Centre for Architecture, 1999), 135–153. ↩

-

Carl (former resident of Khaneh), interview by Samaneh Moafi, Khaneh Esfahan, March 2015. ↩

-

Carl, March 2015. ↩

The houses of Khaneh Esfahan were arranged in groups of twelve around cul-de-sacs. Each detached house accommodated two symmetrical units with the childrens’ rooms located at the back and the living room and the master bedroom located at the front, with ceiling-height windows facing the street. These shared dead-end streets were used by the children as playgrounds where they could kick balls, ride bikes, or play badminton. And the manicured front lawns, as if they formed a uniform green carpet, linked the living rooms to the cul-de-sac. The childrens’ playground was therefore always within the parents’ field of view and it could be monitored from the comfort of the home interior. These interiors, as The Grumman Challenge confidently explained, were equipped with all of the standard furnishings that “one could reasonably expect in the American lifestyle of the mid-1970s.” The items showed were exclusively suburban furnishings: couches, televisions, washing machines, refrigerators, ironing boards, and even silverware and ice buckets. These dining room silverware sets, living room couches, ceiling-height windows, and trim grass lawns were the structural elements for preserving the American family—the human capital of the American economy.

Similar to how the layout of the houses maintained the forms of domesticity considered normative to the American family, the layout of the town supported the behaviours of a “good” American suburban community: curvilinear streets, wide boulevards, and traffic circles regulated circulation and the speed of cars; the perimeter had a diffused border to accommodate expansion at later stages; large parks were incorporated into the master plan to supplement the green lawns; and a kindergarten and a school were set up to, as the film depicts, teach an American curriculum, hold baseball championships, and serve macaroni and cheese. In fact, many of those who taught in these schools and provided community services throughout Khaneh Esfahan were the wives of the Grumman employees who had moved from the United States to support their husbands in their mission.1 The types of labour involved in the Grumman project were, therefore, gendered: educating the Iranian Air Force was the task of the official team and giving the land an American colouration, both in terms of the domestic environment and the culture of the community, was the task of the team’s wives.

-

Carl, March 2015. ↩

Stills from The Grumman Challenge (United States: Grumman Aerospace Corporation, 1976), promotional film, 19:53 min.

But the American-designed town of Khaneh Esfahan was not intended to stay in the hands of Americans—or so the promotional film claimed. Just like the airbase, it was meant to be handed over: once the Grumman employees had finished educating the Iranian Air Force, they would return to the United States and their Esfahan homes would be transferred to their Iranian counterparts. This logic was not new to Iran: it had been introduced decades earlier when housing British workers around the oilfields of Khuzestan province as a way to tame the potential spread of nationalist and anti-imperialist forms of resistance.1 If the transfer of Khaneh Esfahan had occurred as planned, it would have been an educational project in itself because it would have compelled the new residents to learn the American ways of life that had been built into the very fabric—both spatial and social—of the town. A successful mission would therefore have required a handover not simply of the infrastructure but also of the social behaviours that could preserve such an urban model. In other words, it was in this transition that Iran’s human capital would have come to be invested. But the handover never occurred; after just a couple years, the Grumman employees and their families abruptly left, abandoning their Esfahan homes.

In 1978, a revolution swept across Iran and shortly thereafter the country saw the outbreak of the Iran-Iraq War, which would last for eight years. The newly formed Islamic Republic was subject to sanctions by most governments around the world and short of allies, and so it was left with no choice but to naturalize the arsenal that it had inherited from the monarchic regime. The F-14 jets helped Iran win more than fifty conflicts in their so-called spiritual defence against the Iraqi military, whose fleet of Russian-manufactured fighter jets was exterminated. The naturalization of the Tomcats was followed by the naturalization of Khaneh Esfahan with its curvilinear roads, cul-de-sacs, green lawns, semi-detached houses, and furnished living rooms. Given the waves of migration from war-torn provinces to Esfahan in the 1980s, the population had expanded rapidly but without any municipal or regional development plans and with limited access to resources.2 And so the Islamic Republic felt it necessary, as with the F-14 jets, to re-engage with the urban infrastructure that had been built before the Iranian Revolution. This approach was not without risk given that the public might misunderstand it as an affirmation of the social structures and norms—in other words, the human capital—that the town had originally been designed to nurture.

Some thirty years into this process of re-engagement, the part of Khaneh Esfahan that had been developed with semi-detached houses and green lawns was cordoned off and a kiosk was put at the entrance, manned by a soldier assigned to monitor entries and exits.3 Not dissimilar to Grumman’s original intent, the abandoned houses had been given to the Iranian Air Force for its soldiers and their families, however, these new residents had begun to reinterpret, reappropriate, and counter the socio-spatial relationships that the houses were designed to host. The green lawns that once structured the visual connection between living room and cul-de-sac were subject to one of the most extreme transformations: they were almost all taken over by leafy cypresses, rows of pines, mixes of oriental plane trees, and, at times, shrubs of wild roses. Defying their original conception as patches of a uniform green carpet, the lawns were transformed into buffer zones—dense visual barriers that secured privacy for the home interiors. Just as the neighbourhood was cordoned off from the rest of the city, so was each living room from the street. If a wayward stranger entering a cul-de-sac would previously have once been immediately registered by the residents, she could now stroll through these streets and even take pictures unnoticed.

-

The first precedent for this strategy was set in the 1933 oil agreement. John H. Bamberg, The History of the British Petroleum Company, vol. ii: The Anglo-Iranian Years 1928-1954 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1983), 48–50. ↩

-

While there was also substantial migration to Tehran, Esfahan was Iran’s second-largest city and closer to the regions most affected by the Iran-Iraq War. ↩

-

This reading is based on the personal observations of Samaneh Moafi following a site visit. The research into Khaneh Esfahan was part of a larger research into the state-initiated new towns that had been built around Esfahan city in the 1970s and their development after the fall of the monarchy and the rise of the Islamic Republic. See Samaneh Moafi, “Home Rebellion: Housing, Governance and Conflict in Iran” (PhD diss., The Architectural Association (AA) School of Architecture, 2018). ↩

The practice of counter design enacted by the new residents at the scale of the lawn, echoed that enacted by the municipal officials at the scale of the town. While most of the basic infrastructure and the road network were already in place, the government first engaged a collection of engineers to finish the necessary work but briefed them that a problem existed with the cul-de-sacs and that these must be turned into open-ended streets.1 According to municipality’s approach, a series of Khaneh Esfahan’s design features carried connotations of an American way of life and so altering these represented an anti-imperialist urban practice. Then the government divided the undeveloped parts of the master plan into a multitude of small plots and engaged a wide range of private architects and developers, assigning each a parcel and encouraging them to design mid-rise buildings.2 This strategy could not only help differentiate from the part of town reallocated to the Air Force, but it could also increase profits by increasing density.

By engaging many different private developers and assigning them each with no more than a small parcel, the plan for completing Khaneh Esfahan could sidestep the question of what constituted the ideal urban form according to the ethics of an Islamic Republic. Yet, it is more likely that this development strategy foregrounded the financial and human capital necessary to sustain the spatial manifestation of a privatized and neoliberal economy through housing, as is the situation in Esfahan and Iran today. With increasing urban sprawl in recent decades, and similar to how other pre-Revolution new towns have evolved, Khaneh Esfahan is now a neighbourhood of the city more than it is a new town. But aspects of its development model, such as the new town model, the use of private developers, and the parcellation of land, can also be seen in the blueprints of more recent housing projects built by the Islamic Republic, such as the project of Mehr.3

What is to be made of the turn of the green lawns of Khaneh Esfahan into dense gardens? Or the turn of a township in the shape of a green horizontal façade into a cluttered midrise development? Perhaps more broadly, we can ask what is the work of counter-shot in politics of space? If, according to cinematographic structure, the shot is the viewer and the counter-shot is the viewed, then reversing a shot may change the position of each but it will not invert the embedded hierarchy of the relationship. Similarly, the Islamic Republic may have appropriated the American-built houses and fighter jets commissioned by the monarchy, but it inevitably reproduced the hierarchical logic of their design and mission. The Tomcats continued to destroy Russian-built fighter jets and the houses continued to host an elite, gated community. It is time to break with the old dialectical model of the shot and its counter-shot and search for new ways of practicing spatial politics; if not we will continue to reproduce the same violence and systemic inequalities that our cities and homes condition.

-

Jafar (an engineer engaged for the development of Khaneh Esfahan in 1989), interview by Samaneh Moafi, July 2015. ↩

-

Jafar, July 2015. ↩

-

Mehr is the largest state-initiated housing project built in Iran since the 1979 revolution. Today, it encompasses 2.3 million dwelling units spread across the national territory in the form of isolated townships on the peripheries of larger cities. For analysis of Mehr’s development model, see Samaneh Moafi, “A Gift of Compassion: Welfare, Housing and Domesticity in Contemporary Iran,” Journal of Islamic Architecture 9, no. 2 (July 2020): 391–408. ↩