When A Cucumber Is Not a Cucumber: An EU Tale of Customs and Classification

Text by Lev Bratishenko

Day One

At 19:32 on Monday August 12th, 2002, Darius Corneliu pulled into the truck lane at Kiszombor, a small border post between Romania and Hungary. Beside him a limp chain link fence ran behind a line of trucks and towards a concrete cube plastered with signs in Hungarian that he could not read. In the distance, fields weakly suggested cultivation. His Renault truck, a family investment, was carrying a blue 6 metre steel container holding approximately 26,000 kilograms of cucumbers, which came from his uncle’s farm near Bistrețu about six hours away. No, he told the Hungarian customs officer, he did not know how his uncle grew them, whether it was in the field where he played as a kid, or in the rusting greenhouse next to the ditch. Did his uncle practice “Bulgarian gardening”? What was “Bulgarian gardening”? His uncle wasn’t Bulgarian. Really, they were not his cucumbers. Darius was only doing a favour by taking his uncle’s cucumbers to a wholesaler in Szeged. Normally he did not ship cucumbers. He preferred cargo with fewer border hassles, like televisions. He did not understand why the officer—a short man with dark circles under his eyes—was irritated with his paperwork. He only had what his uncle had given him, he explained in broken Hungarian. It should be in order. He was sorry. Bocsánat.

The weary Hungarian customs officer was disappointed with this amateur importer. Sanyi Szilágyi had been working his gate since early that morning and now he wanted to go home, but this guy’s forms were a disaster and Sanyi could not just let him go. He would have to impound the truck. He lifted the gate and motioned Darius to park on the right of a small building about 400 metres up the road. This building served as the office of the Hungarian Customs and Finance Guard, where Sanyi had worked for twelve years, and where he would retire as long as he did not break too many tenets of Act C of the 1995 regulations governing customs law, customs procedures and customs administration, or Government Decree No. 45 on its implementation.

Read more

The office building that Darius approached was in rough shape, but Kiszombor was too small a border post to be a priority for the infrastructure upgrades that began when Hungary joined NATO three years earlier. Big crossings, some with up to twenty lanes, were getting automated disinfection stations, radiation detectors and x-ray machines. Most of them also got a phitosanitary officer or two, trained in handling suspicious produce. At small posts they could only cross their fingers. Kiszombor was 32nd on the list for upgrades.

As he closed his gate and walked after the truck, Sanyi tried to remember the last time he had been required to hold a produce shipment. He could not. Cigarettes topped the list of annual seizures, followed by alcohol, historical artifacts, animals, and finally drugs. Vegetables did not appear. Either they were not considered noteworthy, or they were confiscated in such enormous quantities that their inclusion in the statistics would have ruined the graph.

“Come back tomorrow,” Sanyi said as he walked up to the truck. Darius did not seem to mind, he just shrugged and asked for a ride to Szeged.

Day Two

Darius never came back from Szeged to get his uncle’s cucumbers, but Sanyi would not know this until later. He spent the morning of August 13th at his post stamping the passports of Romanians from Timisoara who were going shopping in Budapest. Sometimes he glanced over his shoulder at the truck, but he did not worry.

Over lunch in Szeged he watched Ferencváros defeat Békéscaba EFC on replay, ate a pork cutlet, and did not talk to anybody. The truck was gone when he got back to Kiszombor.

“Katy,” he asked the receptionist, “who signed the Renault out?”

“Nobody. It’s still there,” she replied, twisting in her chair to look outside. “What truck?” she concluded. “I never saw one.”

Nobody had seen the Renault leave or would even confirm that it had been there in the first place. Sanyi was glad the team was covering for him, but Darius had somehow ditched his cargo and an explanation would have to be made for the bright blue container on the parking lot.

Sanyi had held the truck because the amateur importer was missing a Certificate of Inspection. Since the passage of EU Regulation 1788 in 2001, vegetable shipments that originated outside the Common Market had to be certified by their national regulator, who issued a form that specified the variety, pesticides used, and the average length and weight of the vegetables in question. Sanyi would normally do a quick inspection based on this document, call in to the county office and reference the central database (he would not have his own computer until 2004), then estimate the cargo’s market value. The EU certificate was not really required if the produce was only sold in Hungary, but the government thought early compliance would look good. Yet this amateur importer had not met even the lowest standard: he had not filled out the Romanian origin certificate beyond the word “cucumbers,” misspelled.

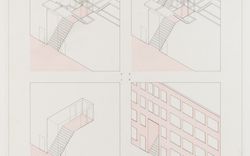

Fortunately for Sanyi, the Customs and Finance Guard had prepared for such an eventuality: there was a flowchart in duplicate, with white and yellow copies, used for identifying the unknown. Selecting the right form required a level of judgement that the Customs and Finance Guard admitted even their junior officers probably possessed, and Sanyi proved them right. He found the one marked növényi anyag. Vegetable matter. The form was organized according to questions about “qualitative,” “quantitative,” or “pseudo-qualitative” characteristics, the answers eliminating other questions, and so on, until all possibilities were narrowed down to one variety approved for Hungarian or pan-European sale. The benevolent authors of the form had included diagrams in case Sanyi had any difficulty identifying parts of plants; roots were drawn on the first page. The form also defined the four types of observation that he was approved to use: single measurement, group measurements, group visual assessment, and single visual assessment.

Sanyi took a ruler, left the container door open for some light, and began. It went well at first and in a few minutes he had narrowed the possibilities down to “gourds” before landing on a square with a recognizable silhouette. Cucumis. Good, everything past this point was a cucumber of some sort. The tone of the document then became impenetrably scientific. The first question stumped him and he had to find a dictionary to look up “cotyledon,” which turned out to be an embryonic leaf. The only leaf he could see in the darkness of 26,000 kilograms of cucumbers was brown and crumbled when he touched it, so he skipped the question. He hoped this would not screw up the worksheet. Next he had to count the length of the first 15 “internodes,” which the dictionary told him were the spaces between leaf attachments on the stem. He could not see any stems so he skipped that question as well. Then there was a “pseudo-qualitative group measurement” question about the “leaf blade attitude.” He thought this was unfair since he had already skipped the first leaf question, and he began to have doubts about the form. This continued for qualitative, quantitative, and other pseudo-qualitative questions about leaf “blade length,” “terminal lobe,” “intensity of green colour,” “blistering,” “undulation of margin” and “dentation of margin.”

Sanyi turned the page over hopefully and found a “qualitative single visual assessment” question about “sex expression.” Back to the dictionary, but he could not tell if the cucumbers had exclusively female or exclusively male reproductive organs, or some ratio of the two. Counting “female flowers” was impossible. Then he had to look up “parthenocarpy,” which apparently meant that the cucumber plant produced fruit without fertilization. These cucumbers had seeds, so he filled in “no.” This brought him a little satisfaction after having skipped so many questions.

Next was a section on fruit, though he was not sure cucumbers were fruit. He decided “fruit length” was “long.” It seemed an appropriate category for the “quantitative measurement” approach, but there were only choices between descriptions. So, “diameter” was “small,” making the “ratio length/diameter” in his estimation “very large.” He was disappointed that he was not using the ruler. He groped at answers to qualitative assessment questions on “shape in transverse section,” “length of neck,” “shape of calyx end,” “ribs,” “sutures,” “creasing,” “degree of creasing,” and “type of vestiture” (Were the cucumbers hairy? They were not.). Following that were questions about “warts,” the “length of stripes,” the “density and distribution of dots,” the “ground colour of skin at physiological ripeness” and “length of peduncle.” This finished Sanyi off. He could not bother to look any of it up.

The only question that had required a measurement was about “fruit curvature.” Printed with a helpful chart, this question noted that Class 1 cucumbers could not bend more than 10 millimetres for 10 centimetres of length. Sanyi wondered what Class 2 cucumbers were used for, then realized that though all of this was interesting and maybe even educational it did not make the cucumber he held in his hand an official cucumber. And he had finished the worksheet. He had no way of measuring the curvature anyway.

Frustrated, Sanyi turned the page over, noticed a lengthy appendix of “Explanations and Methods,” and upon closer inspection realized that many of the questions he had struggled with were not even applicable. He slammed the container shut and walked back to his office depressed.

Flipping through the sloppily filled out forms on his desk, Sanyi felt a growing anger towards the inventor of the worksheet. Some committee at the Community Plant Variety Office had written that thing, had deliberated on it, had considered the people who would use it, and had decided that those people would know what a “peduncle” was. He decided to call Szeged. It meant dealing with Ildi Mészáros, but he was getting nowhere alone. Maybe he could convince her to talk with her boss, the customs king Anatoli Király. Together they were responsible for the Szeged megyei varos, or urban county, and its handful of crossings.

He dialled.

“Post and identification number,” Ildi barked.

“Kiszombor … 13975,” he mumbled, twisting the badge on his shirt so he could read the number.

“Kiszombor is not a number. A number starts the file,” was the reply. Sanyi swore under his breath and rifled through the papers on his desk for the post’s identification code. There was a betting pool at work that Ildi was a computer. Nobody had ever seen her, so the idea seemed plausible.

“212,” he said.

There was silence as Ildi accessed her databanks or filed a nail. “What do you want, 13975?”

“I have a problem. A vegetable shipment has been abandoned.”

“Use a 6-Z form,” she said with the warmth of a lawnmower.

“Doesn’t apply. The shipment is unidentifiable.”

“3-NA then,” Ildi replied, even more coolly.

“Unidentifiable,” he repeated. “Not unidentified. I tried the vegetable matter worksheet already.”

“That is not possible, those sheets identify all vegetable matter.”

“Have you ever tried filling one of these out? I never thought cucumbers could be so complicated.”

“Did you say cucumbers?”

“Yeah, they’re cucumbers alright.”

“You just told me they are unidentifiable.”

“The worksheet didn’t work, but I can tell a cucumber when I see one, Ildi.”

“Don’t call me Ildi. Assuming that you are sober and correctly filling out the worksheet, these are not cucumbers.” She paused to let the logic settle like concrete. “When was the shipment abandoned?”

“Yesterday. No contact information for the shipper. Are you being serious?”

“Dispose of it.”

“Of the cucumbers. These are cucumbers.”

“No they aren’t.” Ildi hung up.

But he knew they were. Sanyi took a cucumber out of his pocket and looked at it. It was bumpy and obscenely curved, twisting around itself with patches of pale yellow at the ends. It was an irregular cucumber. He cut it into chunks and offered it around the office. Everyone agreed it was definitely a cucumber, but there was no taste test on the flowchart.

He went to lunch with Tibor Komárosi, the ex-Olympic wrestler they employed as a security guard. When Tibor proposed they toast the cucumber, he agreed.

Day Three

The next day Sanyi started the paperwork to destroy the shipment. He had to call a trucking company and write a report, which seemed easy enough until he reached the environmental assessment.

When Sanyi had started at the Customs and Finance Guard in 1990, regulations were gently applied, pay was low and sporadic, and staff took home whatever was abandoned or confiscated. If it could be eaten, it was; if it could be sold, all the better; and if it had to be destroyed, there was an area about a kilometre from the post where the ground was black and cracked from fire. An orphanage nearby sometimes complained about respiratory problems, but otherwise you could say the system worked flawlessly.

Things became more complicated when Hungary entered negotiations with the European Union in 1998. Something called harmonization began and the paperwork changed, then increased, and gradually became something he had to take seriously. A year later this would culminate in the 14303/21 Customs and Finance Guard Deed of Foundation by Dr. László Csaba, Minister of Finance, which would state wryly that “The Hungarian Customs and Finance Guard does not pursue any enterprising activity,” in case his employees had other ideas.

For now, the environmental assessment required Sanyi to attest that the destruction of the shipment would not pose a danger due to the release of chemicals or toxins during incineration. This required, among other things, a phitosanitary certificate and a classification code. There was none for ’unknown, obviously a cucumber,’ so he called Ildi again.

“13975. Not cucumbers,” she answered.

“The disposal papers need an identification code. What am I supposed to do?”

“Pass the telephone to a sober colleague.”

Shortly afterwards, the staff at Kiszombor were ordered to take a sheaf of worksheets and a pencil, and form a line at the container. Sanyi fumed nearby and watched the vegetable matter worksheet defeat his colleagues one-by-one.

A cloud settled over the post and the container still sat on the lot. Kalman Kocsis, the paranoid elder of the customs guards who believed the Bolsheviks secretly remained in power, was convinced that the shipment was a test of their collective abilities. Failure meant “Siberia,” he said, weeping, and spent the day packing a bag. Tibor could barely hold a pencil in his meaty hands but insisted on doing his part: he struggled manfully with the worksheet before pounding a dent into the side of the container. Then he went to the hospital. Traffic through the post slowed to an angry trickle as staff abandoned their gates to discuss the mysterious container; those who remained to check papers stopped Romanians, which meant everybody passing through a post between Hungary and Romania, and grilled them about agriculture. Your brother the botanist, where did you say he lives?

Later that day on the way to his car, Sanyi saw Attila Kepes bend over to pick up something on the lot. Sticking out of Attila’s back pocket was a cucumber curled like a pig’s tail. It was too much. Sanyi went back to the office and tried Ildi again.

“I can’t destroy them. The 26,000 kilos of cucumbers I have on the lot don’t exist because of a piece of paper.”

“Then they never entered the country.”

“But they are in the country! I can see the border from here and they are on our side of it. And they are definitely cucumbers. I tried one.”

“There are many borders. The one you see is not the only one. The legal border puts the shipment in Romania.”

“The border adjusts for cucumbers?” But Ildi had already hung up.

He slammed the phone on the desk. It rang.

“Fill out a P-7309 for the removal of the sample or you’ll be fined.”

Day Four

The next day he decided to try higher up the chain of command than Ildi because, he reasoned, the situation could not get any worse. He called the Customs and Finance Guard headquarters, a Beaux-Arts building on Mester Street in Budapest. After giving his personal identification and the number of the post, Sanyi was put on hold. He ate some cucumber while he waited. Then a friendly voice came on the line.

“Good morning valued colleague… Szilágyi!” the voice exclaimed.

“Thanks. My name is Sanyi.”

“This call is being recorded!”

“Is that really necessary?”

“This is regarding an abandoned shipment, correct? Szeged office has made notes on your file.”

“I wouldn’t pay too much attention to those.”

“Thank you for your concern, valued colleague… Szilágyi. Now, how can I assist you in raising the quality of service we provide?”

Sanyi explained the situation. He wanted to talk to somebody who could approve the destruction of unclassified cucumbers. He needed help.

“Thank you for your enquiry. You should submit a written request to the phitosanitary officer for your region.” The voice continued, brightly. “There is no phitosanitary officer on record for your region. Please submit a written request after one has been hired.”

“I can’t, they’ll rot.”

“It is easier to maintain a high level of service if you take your time, valued colleague… Szilágyi. I can suggest that you fill out form CPVO-TQ/061/2 and submit it in writing to us. We will forward it to the European Union Community Plant Variety Office with a request for Community Plant Variety Rights. If your request is approved then the shipment would be identified as a new variety and it could enter the country. You could even name it… Szilágyi!”

“Do I need a phitosanitary officer to certify the form?”

“That is correct.” The voice affirmed, effervescent. “There is no phitosanitary officer on record for your region.”

Sanyi rubbed his head. “Why can’t I just certify the shipment myself? I know they’re cucumbers. Everybody does. It’s obvious, want to come down and look at them?”

“Thank you for the invitation, valued colleague… Szilágyi, but I am not approved to make such a certification. Our protocols exist to ensure the safety and quality of goods entering Hungary and continuing into Europe. The rules as amended by Regulation 1117/88 exist to maintain common quality standards under new production and marketing conditions. The Management Committee for Fruit and Vegetables, the members of which are all approved to make phitosanitary certifications, submits an opinion that must be considered. You can obtain more details on the comitology procedure from Council Decision 87/373/EEC!”

Sanyi hung up, disgusted with everyone including himself. If he had not called Ildi in the first place then he could just dump the shipment. Instead he had followed protocol and now the cucumber situation appeared in his file. He was trapped. He had to destroy the cucumbers legally. Suddenly he felt nostalgic

for the 1990s.

Did anybody at the office know a phitosanitary officer? No, they would already be working for the Customs and Finance Guard. But Katy had a botanist uncle, and that was better than nothing. Sanyi made her call because he could not bear to explain over the phone.

Day Five

A beige Lada in a state of mechanical distress pulled up to the customs office the next morning. The portly, bearded man inside was the retired Dean of Botany at Budapest University, originally from Szeged. The title gave Sanyi hope, and he took the professor inside the container. The professor declared it to be full of cucumbers.

“I’m glad you think so,” said Sanyi.

The professor did not understand this response, but Sanyi explained that he was not making fun. It did not matter that they both knew the vegetables (fruit, the professor corrected him) were cucumbers, because all Sanyi needed was a signed attestation declaring the shipment an official variety of cucumbers and the professor would have a grateful friend in the customs service.

“Your flowchart is stupid,” the professor said. “Go bring me the bag from my car.” When Sanyi came back the professor dumped the bag out on the table and arranged his tools. Holding a cucumber he asked Sanyi what he knew about it and Sanyi had to admit he only knew that it was good in summer soup.

The professor shook his head. He wiped his glasses and started to talk. As he took measurements, he explained that cucumbers grew on vines and belonged to the same family as gourds, which meant they were related to melons, squash and pumpkins. “And other vegetables you will never ask me to drive out here to identify,” he added. The Hungarian word comes from the Greek aggouria, like the German gurke and Russian ogyrets, while English took cucumber from the Latin cucumis. Their global popularity had little to do with their nutritive value, Sanyi learned. Cucumbers were not a particularly nutritious food, consisting of over 90% water, but they did go well in summer soups, the professor agreed.

Cucumbers probably originated in India, and the greatest genetic variety is still found north of the Bay of Bengal. How they got to Europe, and then to the rest of the world, is not particularly mysterious, even if the specifics remain unknown. If Alexander the Great did not bring them back with him, the Romans certainly did. Pliny writes that the emperor Tiberius ordered hothouses built so that he could have cucumbers year-round (they don’t survive a frost.) Then they followed that empire to Gaul and beyond, and one of the colonial powers introduced them to the New World. China ignored all of this to concentrate on its own cucumber cultivation, and still produces the world’s largest crop—over twenty million tons a year.

Modern cucumbers, the professor explained, were bred to reduce bitterness (in the early 20th century they were advertised as “burpless” because the bitter taste was thought to provoke gas) and increase their size. Smaller varieties remained for pickling, but the majority of the world’s cucumbers now came from eight similar varieties.

“That’s it,” he concluded. “An idiotically simple fruit that we will always call a vegetable.”

Sanyi admitted he did not really understand the difference.

“Vegetables are whatever the law says they are, it’s an imprecise category. Some things like peas are technically vegetables only while unripe. Botanically, that is correct, as fruits are the ripened or fertilized seeds of plants. So these,” the professor continued, waving a bitten cucumber at Sanyi, “are perfectly ordinary ovaries. I really can’t imagine how your worksheet misses them.”

Sanyi let the professor take a box of cucumbers as thanks and adjusted the official weight of the shipment accordingly. Including this payment and all the sampling that had been going on, the container’s weight was down nearly twenty kilos. Still, he was glad that somebody was eating them, and he was even more relieved that his ordeal was over. He put the professor’s handwritten statement in a transparent protective sheet on his desk. He did not want to spill coffee on it.

Sanyi spent the rest of the day typing up the professor’s scrawl before he noticed that the form for botanical attestation required an active botanist with a certification number, not a retired one. He went home and lay down.

Day Six

Saturday August 17th, the weekend at last, but Sanyi could not bear relaxing at the bar with the cucumbers on his conscience. That morning he decided that the official organs of the state bureaucracy were not going to recognize the cucumbers, and perhaps they did not have to. He dialled Szeged as soon as he got to work.

“It’s Szilágyi,” he said.

“13975,” Ildi answered. Ildi did not take days off.

“Right. The shipment is still unidentified.”

“I congratulate you.”

On the verge of giving up entirely, Sanyi recalled hearing a radio host discuss the European Union. A formal invitation for Hungary to join was a few months away (it would be made in December) but from Sanyi’s perspective the process was as inexorable as it was mystifying. One could only be patient. Meanwhile there were trips to Brussels for officials in Budapest, training for senior regional officers, and supposedly random compliance inspections for the rest. Most importantly, however, reporters sometimes accompanied officials on these visits.

“I just heard from Nagylak that they had a surprise inspection with cameras and everything,” Sanyi said. “What if they show up here and give a tour for Magyar TV? What’ll happen when they find a container full of mouldy cucumbers, probably genetically modified, covered in god knows what Romanian pesticides? Shall I tell them not to worry, they are still in Romania?” He paused. “There’s an orphanage nearby.”

She was silent for a moment. “Wait,” she said, and hung up.

Ten minutes later an order for the immediate destruction of a container of “unidentified vegetable matter” came through by fax, signed by the hurried hand of Anatoli Király. Sanyi grinned as he held the paper, still warm from the machine. Then he called a trucking company and told them to come immediately in case Ildi checked, and because he wanted to see the cucumbers vanish as soon as possible.

The next half hour was the happiest Sanyi had been all week, and then a familiar looking Renault pulled into the parking lot. It was Darius Corneliu, who was driving in Szeged now. Sanyi was too shocked to ask whether he had papers.

“I hate paperwork,” Darius explained while the winch was pulling the container up onto his truck. “I thought, you know, things would probably sort themselves out.” And he was glad they did. He gave Sanyi a box of cucumbers as a present and drove away.

Cucumbers grown organically can develop with a wide range of forms and gradients of curvature. In 1988 the European Economic Community adopted a law that included new regulations for fruit and vegetables sold directly to consumers. The law included a mathematical definition for the acceptable curvature in the highest class of cucumber. This was intended as a way of standardizing the contents of shipping crates, but an unintended consequence of the law was that, for the purposes of retail, some cucumbers ceased to be cucumbers.

The 1988 law was superseded in 2009, and the new legislation allows for many nonstandard fruits and vegetables to be sold directly to consumers as long as they are labelled “intended for processing.”

Lev Bratishenko is Curator, Public, at the CCA. This text was first published along with a selection of cucumbers in Journeys: How travelling fruit, ideas and buildings rearrange our environment, a book we produced in 2010.