Exploring the Site of the New Punjabi Capital

Text by Maristella Casciato

Between 1950 and 1953, Pierre Jeanneret took about 150 photographs of the site of the city of Chandigarh.

Le Corbusier and Pierre Jeanneret embarked on their first trip to the Indian subcontinent on 20 February 1951, taking an Air India flight from Geneva to Bombay (the city now known as Mumbai). After a stopover in New Delhi, the architects reached the mountain city of Simla, the summertime seat of government during the British colonial period. On 23 February, the two travelled by train to Kalka, from where they were driven in Jeeps to the site chosen for the new Punjabi capital.

The initial encounter with the site had a profound impact on both architects, who were moved by the tranquility of the area’s cultivated fields and the serene majesty of its natural landscape. Two days after their arrival, Le Corbusier wrote to Yvonne, his wife: “We’re on the site of our city, under a splendid sky, in the midst of a timeless countryside…”1 That “timeless countryside” was a gently sloped plain, framed in the distance by the Siwalik, the southernmost mountain range of the Himalayas. Two rivers marked the eastern and western boundaries of the future city’s site, while a seasonal stream carved a sinuous valley in the middle of the plain, which Le Corbusier called a “vallée d’érosion.”2 The area was dotted with small rural villages connected by a dense network of pedestrian paths crisscrossing cultivated fields.

Pierre Jeanneret took photographs of this bucolic microcosm, depicting small earth-and-adobe houses with their ornaments and simple furniture; industrious inhabitants engaged in their occupations; buffalos with long horns; carts with wooden wheels; great mango trees; and tree-lined ditches which served to irrigate the land. The two designers were enthralled by the harmony and abundance of human life they found unfolding in this peaceful yet populated part of the country. On the first page of one of his notebooks, which was later known as “Album Punjab,” Le Corbusier wrote, “Shall we go so far as to destroy the villages?” and, immediately after, commented on the need to “re-establish the natural conditions” and “preserve the peasants’ pathways.”3 Later that day, he wrote of his desire to “maintain the country routes with the trees and their width as they cross through the city.”4 These words reflect not only a European’s thrill in discovering an archaic and almost mythical world pulsating with life, but also a strong will to seize elements of design yielded by the location and the natural way of life of its inhabitants. This discovery led Le Corbusier to develop a firm belief that the site’s system of small settlements and pathways must not be eliminated but rather integrated into the layout of the future city.

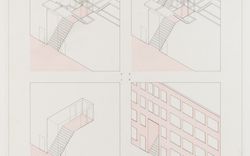

Equally fascinating for the two architects was the discovery of the scenic potential of the site. On 23 February, next to a tiny sketch that captures the angularity of the “erosion valley” with respect to the distant mountains, Le Corbusier noted that “the landscape (the mountains) is very beautiful.”5 On the following day, he wrote: “The mountain range must be an essential feature of the city.” Beneath this sentence appear the first sketches of the future Capitol, embraced in the distance by the Siwalik mountains.6 The course of the “erosion valley” across the plain and the orthogonal run of the mountains provided Le Corbusier with a natural matrix on which to place the Capitol. This nature-defined matrix would also serve as the directional orientation scheme for the city soon to arise.

Further design suggestions came from an excursion Le Corbusier made on the following afternoon. In another notebook the architect carried with him appears the sketch of a pavilion located in the Maharaja of Patiala’s Mughal-style garden in Pinjore.7 The “Album Punjab,” on the page dated 26 February, features a small planimetric scheme captioned as “garden of the Maharaja of Patiala.” Le Corbusier included the garden’s key features—two adjoining square spaces divided into four quadrants and traversed by a central axis—while noting some specific details, such as the length of the bigger compartment, at 350 metres.8 The same internal organization and dimensions appear again, in the first planimetric sketch for the Capitol, which Le Corbusier drew on the same day.

The peaceful agrarian rhythm of life, the landscape’s natural orientation set by the “erosion valley” and the mountains, the Mughal garden in Pinjore: all offered suggestions seized upon by the two designers during their very first days in Punjab. Le Corbusier and Jeanneret would come to rely on this initial insight in their long quest to integrate a modern, new city into a timeless and rural Indian landscape.

-

Letter from Le Corbuiser to his wife Yvonne Gallis, from Chandigarh, 25 February 1951, Fondation Le Corbusier, R1-12-96, also quoted in Nicholas Fox Weber, Le Corbusier: A Life (New York, Alfred A. Knopf, 2008), 542. ↩

-

A sketch of the “erosion valley” as it appeared before the construction of Chandigarh. See: Le Corbusier and Willy Boesiger, Le Corbusier: OEuvre complète, 1946–1952, vol. 5 (Zurich: Éditions Girsberger, 1953), 132. ↩

-

Le Corbusier, “Album Punjab,” Fondation Le Corbusier, 1951, fol. 1, W1-5-3-001. ↩

-

Ibid., fol. 7, W1-5-6-001. ↩

-

Ibid., fol. 17v, W1-5-15-001. ↩

-

Ibid., W1-5-16-001. ↩

-

Sketchbook “E18,” fol. 23, in Le Corbusier, Le Corbusier Sketchbooks, vol. 2, 1950-1954. (Cambridge, MA: The Architectural History Foundation/MIT Press, 1981), no. 331. ↩

-

Le Corbusier, “Album Punjab,” Fondation Le Corbusier, 1951, W1-5-28-001. ↩

A selection of Jeanneret’s photographs of the site of the future Chandigarh was included in our exhibition How architects, experts, politicians, international agencies and citizens negotiate modern planning: Casablanca Chandigarh, held in 2013 and 2014 and co-curated by Maristella Casciato. This text was first published in Casablanca Chandigarh: A Report on Modernization, a book we produced in 2014.