Building Ethnographies

Sarah Lopez discusses remitting as a way of life

How do we use architecture to tell stories and what kinds of stories do we tell? Anybody in the business of architecture history, theory, and criticism has to answer that question for themself. How do we harness the awesome, but often latent, evidence that overwhelms our every moment—the evidence of the built environment around us that shapes our consciousness, actions, subjectivities, and futures? And with what aim? My scholarly focus is, and has been for my career, Mexico and the United States and specifically people on the move, people who emigrate from Mexico and lead transborder, multisite lives, knitting together disparate geographies through their intimate and lived social worlds. As a built-environment historian and a migration scholar, I focus on the history of builders and users more than the history of expertise, professionalism, and technology. And rather than use the terms urban and rural as the dominant framework or analytic category for investigation, I explore the cognitive structures, networks, connections, and relationships evident in material worlds.

I developed my scholarly focus during my graduate thesis fieldwork in Guanajuato, central Mexico, where I visited the compounds of eight brothers who had built eight houses with US dollars. I mapped onto Ramillette, a “Mexican village” the places in the United States where their neighbours were sending money from. Tracing these remittances (payments sent by migrants in US dollars) was a way to interrogate commingled, real-time interactions and conversations about daily life occurring between people stretched across distant geographies. Through this pilot project I formulated questions that continue to guide my research: How does remitting, as a strategy to build new places, fundamentally transform both the place produced and the subjectivities of the producers and the inhabitants? How does remittance architecture reposition the migrant in both Mexico and the United States? How are places mutually constituted?

My research is multisited because you cannot tell a story of transnational migration from one end. I analyze the built environment itself as a primary source, in combination with ethnographic methods in both the places remittances are sent from and the places they are sent to. These building ethnographies are conducted over an extended period of time, documenting, when possible, the envisioning, the execution, the use, and the perception of particular sites. The analysis provides a material analogue—an index—that tells the hidden stories of social change not told in the conscious narratives of individuals and groups. It is often the disjuncture between migrant narratives—their stated aspirations and intentions—and the resulting material form and use of a building that reveals the complexity, ambiguity, and ambivalence of remittance construction as a strategy.

What I call the remittance landscape is the physical features in Mexico’s built environment modified or altered by individual and group remittances of US dollars. This term includes “remittance architecture” within it, which is a narrower focus, and is distinct from “remittance space,” which is a conceptual framework for the sum of all micro and macro processes, subjectivities, spatial practices, and institutional and environmental changes associated with remitting as a way of life. Remittance space as a framework is necessary to capture and encompass the ways in which both sending and receiving places are mutually constituted.

Remittance as a term is most often used by economists to describe money sent over a distance—there are national remittances, international remittances, and so on. But as a verb, it also means to postpone or to defer. So, looking at the landscape of remittance architectures also implies building an understanding of postponement or deferment in architecture—aspirational architecture built to fulfill some desire for the future. I think of the production of the remittance landscape in two phases. There is an informal sending of money between family members to finance private homes or between small migrant groups to finance a communal project, both of which often include material remittances like food, clothes, or medicine. But there is also a formal process by which, through various programs, the Mexican government gets involved in managing the sending and spending of that money, often coopting—unevenly—the transformative potential of a development for its own interests with varying consequences for migrants.

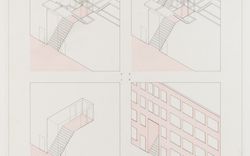

The most common result of the informal phase is the remittance house, which offers endless material and evidence for both speculation and research. These houses appear to be highly idiosyncratic, which raises many questions: How are they made? Do they use standardized building elements or those made in situ? Are components of the landscapes seen and lived in the United States mapped onto them? For example, by setting the house back from the street to create a front yard, a threshold, or by adding a picture window or a carport. Does remittance architecture purposefully distinguish itself from surrounding buildings with extraordinary qualities? What technologies are used to facilitate building over distances? In one case, an architecture plan book was picked up in Florida and used as a template to be replicated in Jalisco, in central-western Mexico. But were there people with the construction knowledge to replicate this plan? What had to change?

This varnished but unpainted brick house was commissioned by a man who lived in Chicago for almost thirty years, Jalisco, Mexico, 2012. Photographs by author.

Aside from such material questions, my research also addresses the subjective and cognitive structures of the people who are envisioning and commissioning these spaces. For example, a man who I’ve known for a long time in Chicago took me to see his brother’s house in Jalisco. He asked his brother, “What things did you pick up in Chicago that you built here in Jalisco?” who replied, “Nothing, this house is one-hundred per cent Mexican.” But the other brother said, “What are you talking about? Of course it’s not one-hundred per cent Mexican. Nobody else here has exposed brick that’s just varnished but not painted, and you have this open floor plan with the kitchen and the dining room, and you even brought the air conditioning unit!” As I watched this interaction, I was learning that one’s own understanding of the impetus and inputs that result in a building can be distinct from what those inputs may actually have been.

Building a remittance house involves technological and material challenges. Before Home Depot or mass-produced products were available, a young girl’s request to have hardwood flooring had to be filled by driving 2,500 kilometres to California to pick it up. And building processes are often shaped by families spread across distant geographies. In one case I studied, a father and his son had to work in a butcher in Oakland to send money on a weekly or monthly basis to his wife and four daughters, living in their remittance house in Guanajuato. What does that mean on a daily basis and how long is this arrangement intended to go on for? Many patterns of remittance houses only emerge in five- to ten-year increments. For example, I assumed when I first saw a structure with four posts and no roof that it was in-progress, but when I saw it again five or six years later and it hadn’t changed, I thought it was abandoned. Finally, years later, I noticed steel bars had been added and I understood that someone was still working on it, was building it at a glacial pace.

To understand the more formalized phase of the remittance landscape, I look at complex public projects financed by migrant groups (hometown associations) through programs like 3x1, by which local funds, often pooled together by migrants in cities like Los Angeles, are quadrupled with Mexican government funds. While the budget of 3x1 is small in comparison with the annual sum of informal remittances, the program is a model for harnessing the business potential of remittance capital. I did most of my research on these larger scale projects in the south of Jalisco, making ethnographic and spatial observations while conducting interviews as a way to get a better sense of the texture of multiple sites, of how these spaces were negotiated on a daily, weekly, monthly basis.

A key and critical type of project in this part of Mexico is the rodeo arena because the jaripeo (bull riding) has remained a tradition since the days of the hacienda. Many pueblos (villages) in the region are still semi-agricultural and animal husbandry is still a way of life. Originally the jaripeos would happen using local cattle and any man from the pueblo could decide to hop on the back of a bull. It was a more spontaneous event that came together within the relationships of the pueblo. Today, rodeos are very much transformed into an economic engine for development and site of norteño (migrant) investment. Of the four arenas shown here, all except one were remodelled with remittances: one has a concrete platform, another brick banquettes, and yet another has steel beams that cost USD 9,000, paid for by people in the United States. But there are also arenas of a much bigger scale, like one in Lagunillas, an ejido town of around one-thousand inhabitants, which was built to fit over two thousand people and is considered incredibly state of the art. It was produced by migrants living in Los Angeles and Nevada who wanted hosting rodeos to be the town’s main economic strategy. But more than profits, I noticed that this investment began to produce a spectacle of remittance based on the commercialization of the jaripeo tradition itself, a spectacle dependent on norteños’ dollars for survival. Rather than encourage self-sufficiency, the remittance rodeo deepened, if you will, the dependency.

So, what does this spectacle look like? It is traditional in these parts of Mexico to have bands with a full range of wind instruments perform at events. These would normally have been local, twenty-person bands that would have charged only a nominal fee. But towns are now hiring national bands with remittance funds. Allegedly, a pueblo near Lagunillas spent USD 75,000 to bring one of Mexico’s most famous bands for their jaripeo, with the hopes of attracting an audience of three- to four-thousand people driving in from multiple states. And this desire for the rodeo to be an economic engine is reinforced by the advertising of national brands next to a sign that details the Mexican government’s contribution to these very small communities and towns. The rodeo is an important moment because, as I’ve been told, “everybody’s united in one place.” “We’ve got people coming down,” Lagunillas locals said, “from Los Angeles, from Nevada, from Colorado, and we’re going to fill this out with both the people that are here and the people from afar.” To handle this influx, the agricultural land adjacent to the arena was transformed into a parking lot, demonstrating a new rhythm created by migration—almost like a different season in a place where the way of life already has strong relationship to seasons.

Another aspect that has changed is the men themselves. They are no longer from the community, but rather professionalized jinetes (bull riders) who travel from jaripeo to jaripeo and risk their lives. In this new context, traditional gendered expectations are performed: young jinetes perform what has been referred to as a “ranchero masculinity” that all villagers used to be tested for, and they do so for the consumption of an audience of norteños returning south as much as for the villagers. The norteño masculinity has, in a sense, been tested by migration itself, by men who cross the border to become a breadwinner and will no longer ride bulls because they have too much to lose.

A band prepares to perform; a sign shows the funds gathered through the 3x1 program alongside an add for Sol beer, Lagunillas, Jalisco, Mexico, 2008. Photographs by author.

Beyond visible changes, local social hierarchies are also redefined by who’s paying for a rodeo. In the case of Lagunillas, the hometown association in Los Angeles and Nevada gave money to the municipal president and the ejidatarios of the village were then made responsible for the daily maintenance and upkeep of the arena. This begs the question: who of these emergent groups got to make decisions about public space and architecture, about what it should look like, and about how it would be managed and maintained? The rodeo example clearly exhibits the tensions that emerge in many public remittance projects between social customs nested in the community and norteños’ aspirations for themselves and that community.

Through the norteños, these material changes in Mexico are linked to material change in the United States. Take the Michoacán social club headquarters in Chicago, a former printing press now used as a community space: it is from this space that people from Michoacán organize and envision change in Mexico and, importantly, it is also through this space that they invest in the brick and mortar that further embeds migrant groups into American cities. This only begs more questions: How do the spaces from which migrants mobilize influence their visions? How might the scale or scope of a migrant project be a response to the American landscape? One of the arguments underpinning the idea of the remittance landscape is that we can’t understand the American city or American urbanism (or Latin American urbanism for that matter) without understanding what happens in Mexican pueblos because they are repositories and barometers of global change. And we can’t assume that migrants primarily invest in the places where they are living, in their host cities—in fact we garner an incomplete picture of American urbanism if we do not view emigrant regions as distant hinterlands of American cities.

Casa Michoacán and Restaurant Hacienda Tecalitlan, Chicago, 2012. Photographs by author.

We know that in the case of Mexico not only migration but also remitting has been happening since the 1920s at least. And historians and sociologists have been asking what about this international migration today is distinct from international migration a hundred years ago. By approaching this question as a built-environment historian, I argue that what is new is that the accretion of remittance building projects over time uniquely shapes the social spaces of migration both here and there, and that social worlds and social life are increasingly structured by the logic of remittance at various scales. According to this logic, distance is normalized and transformed into cultural and social capital and, rather than overcome, distance is incorporated into a way of life that manages separation on a daily basis.

Sarah Lopez presented her research on The Remittance Landscape as part of the 2020 Toolkit for Today: In the Planetary Field, a series of conversations around situating research on site.