Solitary and Social

Yoshikazu Nango on being quantitatively and qualitatively alone

The increase in the number of people choosing to live or spend time alone is a global phenomenon. In this respect, there are, of course, similarities and differences between Tokyo and other cities in the world. As far as similarities are concerned, cities have always been places where people tend to be alone. People from around Japan come to Tokyo to go to university or for employment. A large proportion of tourists visiting Japan first fly into Tokyo before dispersing throughout the rest of the country. Tokyo, like other major cities, is the kind of place in which people are often alone. There are, however, several reasons why it is interesting to focus on Tokyo when thinking about solitude, isolation, and loneliness.

A number of notable inventions intended to create solitary spaces originated in Japan and are very much the product of Japanese culture. Take the Sony Walkman, for instance, it is a device that creates an invisible bubble around its user and provides the possibility to exist in a personal solitary space, even as one moves through public spaces and is in physical proximity with others. Another example of such an invention is the capsule hotel. Capsule hotels and the Walkman were both, coincidentally, brought to market in 1979. Capsule hotels reflect a Japanese sensibility that does not necessarily deem smallness or narrowness to be lesser than. Although capsule hotel rooms are tiny, they still come equipped with all the usual functional amenities found in traditional hotel rooms—just in more compact forms and arrangements. The capsule hotel model, which packs a large number of functions into the smallest amount of space possible, has recently been applied to modern Internet cafés, manga cafés, and karaoke bars across Tokyo.

Karaoke bars have recently been adapted to be spaces that are comprised of numerous solo karaoke booths. This new arrangement can be used in a manner that exemplifies the contemporary condition of living in a city: a group of people may go to a karaoke parlour together, upon arriving, each person goes into their own solo booth, and, after an hour or two, they each come out of their booths and leave together. It is an interesting example of having the possibility to go back and forth between being alone and being in a group. Today, this condition of choice is of central importance in choosing a place to live as well. There is certainly a comfort to be found in being alone and in using one’s time and space as they like, however, the fact that there is no one else around can easily bring about a feeling of loneliness. It follows that it is important to be within a certain distance of others—or at least have the option of being able to easily connect with others whenever one wants to do so. The prevalence of this desire is clearly evidenced by the number of people who currently chose to live in shared housing in Japan and more and more across the globe. In Japan, there is housing that is purpose-designed to be shared: rooms for individuals, primarily bedrooms, provide privacy, but when occupants wish to spend time with one another, there are common areas in which they can gather and socialize.

Moreover, with social media, individuals can customize and optimize their information environments, such that they only virtually see the information they want to see and only meet the people they want to meet. To formulate it differently, individuals can easily avoid information and people they do not wish to encounter online. The evolution in communication technologies has also created important possibilities for customizing our physical environments. Our “always-online society” is able to connect to anyone, at anytime and anywhere by means of a Wi-Fi connection, but these connections are made by the creation of physical isolation by mobile devices such as smartphones and tablets that erect invisible partitions around anyone, at anytime and anywhere.

This customization made possible by our “always-online society” can also have negative effects: people have become more prone to becoming anxious when either physical or virtually disconnected from others and it puts us all in a state of mutual surveillance. So, on the one hand, there is the feeling of always wanting to be connected to somebody, and, on the other hand, there is the stress of always being connected to and, therefore, being watched by somebody. This struggle between wanting to be connected and wanting to disconnect is an integral part of contemporary society.

A problem arises when we equate all forms and degrees of disconnection with isolation, rather than acknowledging that some versions may stem from this widespread desire to have moments of disconnection in solitude. “Isolation” refers to a rather objective state on the subjectivity–objectivity continuum. It often refers to being excluded or marginalized from a group. On the other hand, “solitude” is a subjective state that can be interpreted either positively or negatively, the positive side being that it allows for introspection and the negative leading to the feeling of loneliness. The negative connotation of the word is the basis of the problem of solitary deaths, which typically refer to elderly people dying alone and from a lack of help and support from families or social circles, and that are numerous in Japan. Similarly, social withdrawal is gaining more and more prevalence in the country, and though often presented as affecting only young people, it affects all demographic groups. While isolation and solitude are certainly different, it is possible that a person can gradually start feeling solitude after having experienced isolation and that a person who likes to spend time in solitude may well end up being isolated.

What needs to be acknowledged is that there is a sort of violence performed when applying the term “solitary” to describe individuals. This is because the term can be used to qualify nearly anyone, whether they be young or old, live in urban or rural areas, are married or single, or are in isolation or in solitude. All the differences that exist between people who are labelled as “solitary” are flattened by the term—an act of categorization that is primarily done to collect and group data from which to analyze social trends. It is clearly necessary to approach the trend qualitatively rather than quantitatively in order to correctly detect and understand loneliness. In modern cities, everyone, even if they live with a partner, with family or with roommates, has moments when they are alone as they go about their lives. Accordingly, it is important to consider a broad spectrum of lifestyles in which people spend time alone rather than to merely examine the state of people being quantitatively alone.

Solitary spaces in modern cities are often found near transit hubs such as train stations. Intermediate spaces such as these are those located between one’s home and one’s school or workplace. In Japan, many solitary places such as beef-bowl shops and standing bars have traditionally been perceived as male-centric places. This was based on the male breadwinner model, in which men would work outside the home and women were homemakers—a model that had long been the norm in Japan. Due to a lesser adherence to this model and the rapidly increasing number of “ohitorisama,” a term which refers mainly to unmarried—by choice or not—women in their thirties and forties, since the early aughts, the number of solitary spaces that cater to single women has been on the rise. As more and more women enter the workforce, remain unmarried, and earn more than enough to cover their living expenses, they have come to represent a “premium group”—to use marketing speak. It is for this reason that various services and products, such as wine bars, travel tours, beauty salons, and apartments, have been specifically developed for single women in Japan.

This is of course tied to society’s embrace of capitalism and to the economy shifting from prioritizing mass production and mass consumption to an economy in which the production of a wide variety of products in small quantities according to individual preferences has become not only possible but desirable. The availability of services and products that can be customized according to individual preferences is increasing exponentially. However, it is important to keep in mind that this freedom is only supported by economic principles and a capitalistic logic.

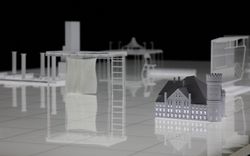

Seemingly outside of this logic is the ever-shrinking size of housing units for single occupants in Japanese cities, especially in Tokyo. However, it is important to recognize that these units are only small when considered as stand-alone housing units. In the past, one’s personal lifestyle in the city involved the frequenting of a network of facilities, such as public baths, laundromats, and cafeterias, rather than having all of one’s needs fulfilled within and by one’s home. It was only recently that all these functions became internalized in the private dwelling. The kind of urban lifestyle that these small units for individual occupancy imply is a return to this earlier model, in which the entire city becomes one’s home. For example, when convenience stores became commonplace in the 1980s and 1990s, more and more young people living alone stopped equipping their homes with microwave ovens and refrigerators. Such decidedly urban lifestyles could only emerge because they were supported by functions, previously only found within one’s home, such as food preparation and storage, that became available outside of the house, in places such as convenience stores. When these small housing units are understood as part of a rich urban ecosystem composed of various facilities, they begin to feel expansive, and when its occupants are considered in this same context, they can be understood as simultaneously solitary and social.

This text was adapted from an interview with Yoshikazu Nango conducted as part of the research for the CCA’s film When We Live Alone. It is published as part of the Catching Up With Life project.