Shared Worlds

A Conversation with Rodrigo Kommers Wender, PLOT

Giovanna Borasi, Kate Yeh Chiu, and Albert Ferré spoke with Rodrigo Kommers Wender, editorial director of PLOT magazine, about their recent issue on collective forms of living, Mundos compartidos: redefinir los límites de la domesticidad. This conversation is published as part of the Catching Up With Life project.

- GB

- I recently read an article in the New York Times about parents in North America now moving in with their kids because they can’t afford housing anymore and they don’t have retirement plans. We always speak about young people living with their parents, but now we have a kind of opposite. The idea of our project A Section of Now is to try to understand the extent to which architects play a role in actually anticipating some of these issues or reflecting them. When you gave me PLOT 50, on shared housing, I felt you were asking the same question. How can architects play a role?

- RKW

- In North America, there’s quite a paradox: property defines everything, but a vast majority cannot access it. There’s no doubt that we need a paradigm shift to face all these challenges and depart from this materialist, symbolic construction of the world we live in.

For this issue of PLOT, one of our initial thoughts was about the Italy: The New Domestic Landscape exhibition, curated by Emilio Ambasz in 1972 at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, where he presented a catalogue of projects by the radical Italian avant-garde of the late 1960s around the idea of new domesticity as a critique of capitalist logic. In our issue, we were interested in exploring new forms of domesticity in the post-digital era, when relationships and the idea of traditional families are blurred by countless factors such as job flexibility, increasing demographic density, the ecological crisis, the distribution of wealth, the new dimensions of digital life, and also, the changing role of women in society.

Maybe there is also a need for a reconfiguration of spaces and programs because of the growth of life expectancy and the redefinition of affections. This idea of the mama, papa, and sons and daughters—it’s an idea that really doesn’t fit any longer for the vast majority of the world. The rise of shared living has a lot to do with that. We start the editorial with a quote about this. It was from Yingxuan Teo, a former resident at SPACE 10, who said that the rise of the so-called collaborative economy, together with global resources being very suddenly depleted in a rush of population growth, forces us to rethink the concept of ownership and participation in everyday life. Including in housing, of course. What opportunities could cohabitation offer us?

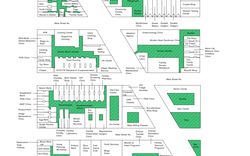

Petrus Hendrik (Sier) van Rhijn. Typical floor plans of a 380-unit housing development with shared facilities, Jan van Galenterrein Amsterdam, 1981-1985, Het Nieuwe Instituut. Image included in the One Shared House 2030 project, Anton & Irene

- GB

- You were referring to new kinds of family. I think something we are very used to on social media is that you create the kind of group you want to talk to, the people who share your affinities or interests or whatever. It’s so normal to share a digital space with people you don’t know. What will the consequences be when this becomes a life thing?

- RKW

- Sometimes digital life brings us together, but sometimes it also remains impersonal. We do not need, as before, to share the same physical space, to have some great bond with someone, for example. One of the articles in the issue is about One Shared House, a research project by Anton & Irene and SPACE10 that compiled answers to a survey on how we will live in 2030.

- GB

- So what are the architectural typologies that come out of this?

- RKW

- The project constructs a constellation of desires and a questioning of how much you are able to share. There’s sharing of service, common rooms, workspaces, but also the autonomy of decision-making about where you live, how you share the ownership of spaces. It’s a very extensive survey. I talked about the issue with some friends not in the architectural field and some of them just saw this as only an economic issue: you cannot pay for a house, so you unfortunately have to live with someone. The question of property and inheritance is at the core of our society, and the idea of traditional families is the base of capitalism; it’s not enough just to change the way we live in our houses. Traditions and life are made of rituals; you need a transformation of some kind. But in order for that transformation to be possible on a big enough scale, there has to be the need or desire. With the COVID crisis, you now have new needs to address, so you change many things—it’s kind of paradoxical to talk about sharing worlds in a moment of distancing.

- AF

- I’m fascinated by your framing of sharing in the context of an environmental crisis and therefore also of a crisis of capitalism. But, in the introduction to the issue, you also write that sharing is part of a culture that looks for new experiences and that reflects a political position engaged in a collective effort.

- RKW

- There are a lot of co-housing projects that are just products selling you a new modern way of life. This is just a new version of consumerism. We were more interested in projects that have broader implications, with changes in modes of being and with political interests. To really change how we live together, you really need to reinvent new modes of property ownership also, to think in a different way.

Both the works and texts in the issue are crossed by many heterogeneous vectors. We weren’t only interested in architectural work, because you need to ask: How can you be more potent politically, in Spinoza’s understanding of the word? The projects we selected, beyond their formal expressions, propose a subjective reconfiguration of politics and of different worldviews. In 1972, Archizoom declared that design itself wasn’t capable of freeing us from oppression and that the political does not reside in the form of the house or in the form of the city but in the way we use them. So, I think that you don’t even need to change all the programs—you don’t need to make a completely different architecture—but you do need a completely new way of using these spaces.

- GB

- You made the point that the discussion about sharing should be separate from that of affordability. I was wondering if, because you make a clear distinction between the desire and need for sharing, if sharing might be an answer to the economic crisis and to a need to rethink affordable housing. We don’t need to always imagine affordable housing as a kind of small, cheap, separated unit.

- RKW

- I wouldn’t say that this is the solution for the future of housing, but I’m sure that there’s an opportunity here. The idea of family as the base of the individual house is disappearing in a certain way. I don’t know how many people have two kids, are married as man and woman—I don’t know, it’s not the rule anymore. I’m gay. I don’t have kids, for example. I live alone in a house that is not mine, a house that I rent, that I couldn’t buy today. Is there a possibility for me when I’m older to share a common house with friends in the same situation and share our lives and support each other? Why not?

In the magazine, there is a project for a three-generation house in Amsterdam designed by BETA office for architecture and the city. It’s a house with five floors that have different units, but all units are connected. When you have elder people, younger people, and people who need to go out of the house to work, the elder can care for the younger. You create a way of community, of sharing things—not only spaces but also some aspects of life. There are amazing examples that make the world better in that way. Everyone wants to have a good house, to have friends, to have romantic relationships, to have whatever, and these kind of possibilities of sharing are, for me, examples of ways you could think of the future on a broader scale.

Of course, the works in the magazine are all from Europe and Asia. You have nothing similar here in America, Latin America. Even in the United States, you don’t really find these projects. So, there is also a cultural phenomenon at play here. Actually, one thing we have published from Latin America is Anna Puigjaner’s essay about community kitchens in Lima, “Bringing the Kitchen Out of the House.” These make for a very interesting way of sharing things. Not a house but, in this case, a kitchen, because the kitchen determines the way the family is structured, the role of women. This commune also provides more affordable meals, a place where you could share cheaper meals. These spaces have also been transformed into spaces of political thinking. This shift of the kitchen is a way of empowering the members of the community.

- GB

- We have seen other architects work with these ideas of access, taking out a function of the house, which, until then, had been somehow private or individualized. When you take it out, you then need to share it. There is a kind of design intentionality in not only deciding what we share in the design of the house, but also in taking out functions from private space and forcing people to share. We hear a lot about shared offices and the potential power of the corridor. While much of contemporary architecture is built with the idea of rooms that just connect to one another without corridors, if you then start to look from at it this social, shared point of view, maybe the corridor or staircase become the only spaces where you would actually meet a neighbour. Do you think that giving importance to these small, shared spaces would have an effect in changing social relationships?

- RKW

- Yes, let’s not forget that the vast majority of the city is built by anonymous architects and that in the current proliferation of monoambientes or studio apartments there is no singularity and no social dimension. The atomization and individualism at the base of our models of life and our built environments—I think they also determine the modes of perception of one’s self and of others. It’s not only a question of changing these models, but you also need to change with them. Bruno Latour said that the big question is: How should we live collectively today? The world is continuously articulated and defined and constructed by us, through political practices, cultural practices, scientific practices, and so on. I don’t know how much reality will make us change and how much we are changing reality. There are these shifts and changes in the programs of builders and architects, but, somehow, we also need new ways of thinking about ourselves.

- KYC

- So much of the change that needs to happen has to be ideological—we’re talking about traditions or rituals, economic systems, religious systems, political systems that shape how we live and what we’re comfortable doing—I wonder how many of the projects in the issue are private, client-driven. It seems like, in order to achieve a project that is so open to a “new” way of living, you have to have a client that is fully bought into this belief system. If architects want to work at a broader scale beyond just the one-off project for that very special client—do they also need to become activists, social workers, policymakers? Does the job expand to include designing policy, protocols, ways of living, rulebooks, etcetera?

- RKW

- Well, I don’t really know how this could happen on a broader scale, because of course what you said is true. Somehow, these are very special clients, because also they have the interest, the desire, and they know what they want, and they know the way they want to live. I think that’s not happening everywhere to everyone, of course, and typically architecture is just about the need to solve a problem—you just need to build a roof to provide shelter from the rain—so it’s also true that all these projects are for lucky people in the world that can afford these kinds of projects.

It will also change the way the offices work because if you need the participation of the client in projects like these, they become almost co-designers, in a way. So, of course, there is a knowledge that is shared; the expectations are probably different. And in this kind of relationship there is also the need to rethink the role of the architect.

- GB

- The last question is very much a COVID question. Here in Montréal, student housing was closed down early because the level of sharing was so high that it was impossible to manage the buildings. Will the architects working on sharing as prototypes put aside this work now? Maybe the difference, in the future, will be that you will just pick the people. You need a support system, especially if you live alone. If you have ten friends that are all isolated now at home and they seem fine, why not go on living together?

- RKW

- This moment shows us that doing things collaboratively is an enormous necessity. There is a need to create a support network, not just economically, but also one about caring. There is a quote from Peter Sloterdijk I cited from Bubbles, “Let no one enter who is unwilling to praise transference and to refute loneliness.” In this individualist society, I think that to refute loneliness is a political act.

I think that people don’t need too much. Of course, the concept of needs is very flexible: my needs are not your needs. But I hope that this moment particularly encourages us to be more willing to share in many ways—in the distribution of wealth in the world, for example, in the way you collaborate with each other, and the way you care about those who live near you and the friends you made, the different kinds of family you create, you build, and construct with each other. I think that that’s one way to be less empty. I don’t think that a man is an island.