Utility Amenities as Minor Infrastructures

Jesse LeCavalier explores access to food as an urban right

In an early scene of the 1986 film True Stories, David Byrne, the film’s director and writer, narrates from behind the wheel of a large automobile and describes the US interstates as if seeing them for the first time: “They’re the cathedrals of our time, someone said…. Not me.” The someone, in fact, was Aldo Rossi who wrote, “To those who travel the great highways of the Midwest, silos appear like cathedrals, and in fact are the cathedrals of our times.”1 However, Rossi was not describing freeways but grain elevators, one of the striking visual manifestations of North American food production and distribution systems. The conflation of distribution systems (the freeways) with monumental storage (the grain elevators) points to challenges of apprehending infrastructure—the most visible manifestations tend to be only one small component of much larger and significantly less discernible systems. Increasingly, and due in no small part to the decentralizing tendencies of the freeway systems, food infrastructures have migrated further from a collective field of vision to the urban periphery and hinterland.

Grain elevators, of course, have been the subject of numerous forms of architectural and urban scrutiny, lauded for their economy of means and for the poetic merging of form and function into an abstract expression of modernity. And while many of these examples are from the early part of the twentieth century, the impulse to monumentalize commodity storage is alive and well; evident, for example, in the Swissmill Tower in Zurich by Harder Haas, completed in 2016. An exception to the migratory dynamics through which land value puts pressure on industries to seek out more infrastructurally convenient and less expensive sites, the Swissmill complex occupies prime real estate in the centre of the city. Integrated production and distribution facilities combine to make the urban location feasible. The city of Zurich itself has also been a willing supporter Swissmill’s historic location and local freight connections, making the transportation of milled grain possible. In other words, an enviably unique merger of location, history, and political will.

Swissmill grinds nearly eight hundred tons of grain a day, and the tower’s forty-five silo cells can store and distribute roughly thirty percent of the country’s grain demand.2 Indeed, a portion of the stocks held in the Swissmill Tower are part of the country’s food security stockpiling policy in which four months of staples are held in reserve throughout distributed locations.3 In this sense, the monumental and fortified architectural idiom of the installation is consistent with its representational task of communicating security and solidity. While the Swissmill Tower is impressively abstract, it is not without articulation. Different faces of the building are embellished with expressions of structural and organizational performance including buttresses and apertures. These function to confer some legible scale to the installation—even at 118 metres, the openings on the final floor are recognizable as windows, the striations along the vertical face mark the elevator cells. However, while the Swissmill Tower plays a public function within Switzerland’s program of compulsory stocks, its urban disposition does not express publicness—quite the opposite. Given the security requirements of the building, this is an understandable architectural response to the city. However, it raises the question and prompts consideration about how a more completely public system of food distribution might take shape in contemporary urban contexts.

-

Aldo Rossi, “Timeless Cathedrals,” trans. Diane Ghirardo, in Lisa Mahar-Keplinger, Grain Elevators (New York: Princeton, 1996). ↩

-

Kian Ramezani and Felix Burch, “Dubai und Schanghai können einpacken: In Zürich steht der höchste Kornspeicher der Welt Mehl für JEDES DRITTE Brot der Schweiz,” watson, 13 November 2015, https://www.watson.ch/wirtschaft/schweiz/905205405-in-zuerich-steht-der-hoechste-kornspeicher-der-welt. ↩

-

“Compulsory stocks,” https://www.reservesuisse.ch/compulsory-stocks/?lang=en. ↩

The Swissmill Tower, as both built element and as expression of a comprehensive strategic reserve plan, offers a useful point of comparison for the food landscape in the United States. It bears stating that it is impossible to compare the two countries on even terms but, even so, the Swissmill Tower serves as an example of food infrastructure playing a role in the construction of the city’s infrastructural landscape and consequent identity. In the United States, by contrast, food stockpiling has generally been offloaded to individuals, in keeping with the country’s fraught relationship between federal and local policies. As has been evident during the COVID-19 pandemic, such policies contribute to the already wildly uneven resource distribution in the US. Moreover, the food system itself underwent a series of transformations and consolidations in the 1960s and 70s that are still being felt. According to sociologist Andrew Deener, “Changing profitability methods locked into the distribution infrastructure and created repercussions for consumers living in older urban territories. The transformation of the distribution system gave rise to the food and retail deserts of the 1970s that continued for decades.”1 Media historian John Durham Peters points to such path dependencies as a fundamental symptom of infrastructure and suggests that “Often [infrastructures] are backed by states or public-private partnerships that alone possess the capital, legal, or political force and megalomania to push them through… Because of their technical complexity and costs, infrastructures are often cloaked from public scrutiny, their enormous risks and unintended consequences shielded from open debate.”2 While the Swiss context might be an exception to Peters’ claim, it resonates in a US context where the reckoning with the legacies of infrastructural megaprojects continues.

In looking forward, both Deener and Peters point to the mundane and even boring aspects of systems as leverage points. For Deener, “For a system to change, actors have to turn novel methods, tools, and techniques into interactive and compatible ties. They have to convert specific technical knowledge into routine exchange sequence, organizational cultures, predictable supply chains, and profit-making conventions.”3 In other words, novelty must become routine, but that process might be able to smuggle more profound realignments. Technology and technique here become alibis to bring about more fundamental shifts in value. For Peters, becoming fascinated with the boring is also to appreciate its transformative potential: “Redundancy may be boring, but the essence of robust systems is backup options.”4 This is of course not news to any student of network behaviour, but Peters’ call for a critical turn to “infrastructuralism” is significant because it signals the need for a larger collective engagement with otherwise “technical” systems. To do so would be a step toward addressing the complex entanglements that emerge from the numerous long-term problems of social and environmental justice, especially in urban areas.5

-

Andrew Deener, The Problem with Feeding Cities: The Social Transformation of Infrastructure, Abundance, and Inequality in America (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2020), 16. ↩

-

John Durham Peters, The Marvelous Clouds: Toward a Philosophy of Elemental Media (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2020), 31. ↩

-

Deener, 15. ↩

-

Peters, 36. ↩

-

Deener, 20. ↩

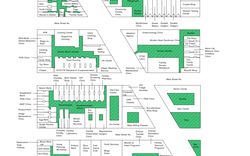

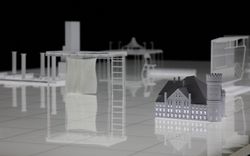

By humanizing and ritualizing its mundane operations, food infrastructure could become civic infrastructure and thus an essential part of everyday life in the city. Brooklyn Amenity Utility is an exploration of the possibilities of infrastructure invested with this otherwise kind of visibility and contingency. The project explores the transformational potentials that would ensue if access to food was thought of as a utility, similar to potable water, electricity, or waste management. It argues for access to food as an urban right by positioning food infrastructure as an adaptable condition and a catalyst for locally determined responses to improving food equity. A network of “amenity utilities” provide food staples to everyone in the city at no direct cost to them, while various amenity utility nodes function as sites that mobilize social interactions through the complimentary provision of raw ingredients, prepared foods, and infrastructure to make and share meals. The project looks to the commonality of food as an avenue to work against increased polarization by instead focusing on the possibilities of convivality and abundance.

Conceived of as an institutional entity with an architectural and infrastructural identity and implementation mechanism, the Brooklyn Amenity Utility attempts to ground the industrial dimensions of food production (in this case grain milling) through an attention to their spatial, technological, social, and ecological requirements. It embraces these aspects and sees them as sponsors for a wide range of community uses that are built within the infrastructural dimensions. The backbone of the project is a series of prototypes that perform different roles within the larger network, such as storing, processing, milling, and distributing—combined in different ways to achieve economies of scale past a certain threshold. The prototypes support “armatures” which in turn support a host of locally determined functions.

The prototypes’ spatial and tectonic expression engages histories of industrial and bureaucratic architecture. Not intended to recede as much as to invite completion, the prototypes aspire to a look of “in-betweenness” as described by Sianne Ngai in her exploration of contemporary aesthetic categories: “Whereas beautiful is ‘final,’ interesting is in media res, ‘on its way’ to a ‘there’ whose actual destination is uncertain… Yet because ‘interesting’’ lacks the specific characteristics that enable the ‘voiding’ of other aesthetic concepts, it also seems capable of coexisting alongside or being coupled with other aesthetic values in a way which other aesthetic values are not.”1 In Ngai’s formulation, the interesting flickers between engagement and boredom but nevertheless compels some form of attention, consideration, and even analysis. While her focus is on cultural production, the articulation of the interesting overlaps with discussions and definitions of infrastructure. Thinking infrastructure through this lens in turn invites consideration of its affective possibilities. In the context of the Brooklyn Amenity Utility, the formal definition of the prototypes and armatures should comprise a kind of “low resolution” architecture that orients the completion of each site without over-determining them.

-

Sianne Ngai, Our Aesthetic Categories: Zany, Cute, Interesting (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2015), 152. ↩

The Utility operates through a series of protocols:

- 1

- Available and eligible sites are identified by looking at empty parcels maintained or otherwise managed by a municipal agency (e.g. the New York City Department of Sanitation (DSNY), etc.). In this respect, the project is interested in activating underused parcels through municipal vectors rather than assuming private development as the engine of transformation.

- 2

- Once a parcel is identified, a suitable prototype is then selected. All prototypes include some form of alimentary provision but, depending on the size and situation of the site, will have different combinations of storage, processing, and distribution function. Prototypes share a common material language of seriality and formal repetition/variation characteristic of industrial vernacular buildings.

- 3

- As the prototype is sited in each location, an additional armature is developed based on the organizational logic of the prototype and site. These armatures help to define and organize each location through the provision of circulation and utility access.

- 4

- With the prototype/armature thusly sited, a “Request for Proposals” (RFP) is issued to the community, particularly local entities active in community organization. The RFP solicits ideas for land uses that could be especially useful, meaningful, or otherwise valuable to local residents. These land uses are imagined as non-for-profit community-based amenities that have an infrastructural or civic orientation that might help to meet local needs, such as green space, gathering space, health support, reproductive labor support, or new forms of programs still to be developed like common kitchens.

- 5

- Either on their own or with the support of the Amenity Utility, proposals are refined and then democratically selected from within the community. The general idea is to use the initial impetus of alimentary infrastructure provision to provide opportunity for local appropriation and the productive channeling of municipal funding. The architecture is meant to be productively neutral in order to provide the support for locally desirable uses to flourish. In this sense, the prototypes act infrastructurally as they recede while the more visible and active public dimensions are foregrounded. The armatures of the prototypes provide some level of initial bias that provides sufficient constraints for the RFP responses to react to.

The municipal role of the Amenity Utility is to facilitate local determination, not to catalyze gentrification through the introduction of commercial indicators like galleries or expensive coffee shops. The project is imagined as a possible means to improve local conditions without increasing land prices and producing displacement.

These prototypes attempt to engage the challenges of food exclusion zones by developing a middle-out approach. Amenity Utility nodes become reliable sources of healthy food but also become sponsors for programmatic innovation determined by the specific needs of the local community. Formally, each site will be recognizable as part of a system because of its prototype and armature, but unique because of the locally developed form, which has the potential to be wildly diverse. By proposing a distributed network of food provision as an alibi and sponsor for civic transformation, Brooklyn Amenity Utility argues that minor forms of infrastructure could be pathways to promote new forms of collective expression and shared experience.

The author would like to acknowledge the support of Jake Rosenwald (project team), Willis Kingery (graphic design), and Robyn Metcalfe (food systems consultant) for their work on Brooklyn Amenity Utility, as well as the John H. Daniels Faculty of Architecture at the University of Toronto for their support of the project.

Brooklyn Amenity Utility is featured in our current Main Galleries exhibition A Section of Now, with exhibition material printed at a83 in New York City. The project also appears in our upcoming publication of the same name.