A Space for Removed Monuments

Mario Gooden on memorials, monuments, and purgatory. Photographs by Giulia Spadafora

In the essay “Of Other Spaces” published in the spring 1986 issue of Diacritics, French philosopher Michel Foucault defines the concept of heterotopia as akin to a counter-site of contestation and inversion. According to Foucault, a heterotopia is paradoxically a real place, but it exists outside of all places. Existing between the conceptual and the physical location in space, a heterotopia is not dependent upon a building typology or form, but rather it exists in relationship to a condition among a set of relationships such as crisis, trauma, deviance, contradiction, accretion, aberration, exclusion, and compensatory subjugation—that is the subjugation of others as a form of recompense for a self-perceived deficiency.1 While Foucault ruminates that certain kinds of colonies functioned in this manner such as Jesuit missions in South America, where the daily existence of the colonizers and even much more so for the colonized Indigenous population was regulated at every turn, there should be no question during the current moment of global social revolution that the construction of race and its attendant racism contemporary to the European colonial project has a deleterious effect and exposes that the European is also raced. For the European position of superiority as articulated in the dialectic in Hegel’s The Philosophy of History is dependent upon assigning a position of inferiority to non-Europeans: Negros, Asians, and Indigenous peoples. Furthermore, as author Toni Morrison explained in a 1993 interview, “Don’t you understand, that the people who do this thing, who practice racism, are bereft? There is something distorted about the psyche…It’s is a profound neurosis…it feels crazy, [because] it is crazy.”2

In addition to the colony, the cemetery serves as another heterotopia for consideration. As Foucault explains, in Western culture, the cemetery has always fundamentally existed. Originating in the centre of the city, adjacent to or surrounding a church, the cemetery also existed in the form of tombs beneath the church or within the church itself. At the end of the eighteenth century as Western civilization grew less assured of its belief structures, the cemetery migrated outside the border of cities, as emphasis shifted away from the soul to that of the dead body and its association with illness. In a certain manner, the cemetery not only became a heterotopia but also a purgatorial location between death and an afterlife. Recently, in the United States, cemeteries have increasingly become new sites for the removed confederate monuments to Civil War figures that were erected in city centres and town squares in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries as a reaffirmation of white supremacy and infliction of trauma to Black Americans extending to colonial era enslavement. While some such monuments had previously been located in cemeteries, the heterotopic ambivalence of these sites somewhere between “Paradiso” and “Inferno” is a recognition of these monuments and their protagonists between former glory and current damnation. Rejected by formidable institutions, local and national museums such as the Smithsonian Institution, the cemetery is a counter-site, a non-typology, and an anti-building for these artefacts.

Other contested monuments and memorials to colonial figures across the United States, Canada, Britain, and the African continent have been removed, shrouded in tarps or other forms of concealment, and relocated to temporary and sometimes secretive storage locations. The decolonization of public space through the removal of these artefacts to provisional warehouses is also another example of a heterotopic purgatory. Although the warehouse is a site of accretion and the accumulation of time similar to Foucault’s description of the museum or library, it lacks the cultural and epistemological foundation that serves the development of society. It owes its condition to the supply chain of neoliberal capitalism that consumes, transforms, and excretes various kinds of byproducts.

The question of what type of architectural space is suitable to eventually house, preserve, and access these monuments is a question of society’s values and how it comes to terms with its history. While on the eve of the fiftieth anniversary of the Nazi takeover of Germany there were historical exhibits, theatre and art productions, publications, and public discussions, there were no displays of monuments or memorials to the Nazi era in Germany, because they do not exist. The unofficial slogan for Germany’s 1983 recognition of its Nazi era was “Collective Guilt? No! Collective Responsibility? Yes!”1

-

Susan Neiman, “There Are No Nostalgic Nazi Memorials,” The Atlantic, 14 September 2019, https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2019/09/germany-has-no-nazi-memorials/597937/. ↩

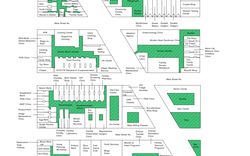

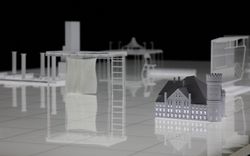

Forty-five years earlier, on 11 November 1938, the architect Giuseppe Terragni presented his design for the Danteum to Mussolini at the Palazzo Venezia in Rome, shortly after Mussolini had signed the “Pact of Steel” with Hitler and the Nazis. The Danteum was designed as a “celebration of the words of Dante, considered a primary source for Mussolini’s creations” and other similar nationalist monuments to glorify the arts as a function of State ideology.1 Conforming to Dante’s Divine Comedy, the Danteum contained three main spaces: Inferno, Purgatorio, and Paradiso. Terragni’s design for purgatory contains seven square terraces derived from overlapping proportions and dimensions of where the roof mirrors the floor and contains seven square openings to the sky. As the space of penitence in Dante’s Divine Comedy, it is a space of liminality caught between the reflexive conditions of ground and sky and the play of geometric (in)determinacy. Although it was never built, perhaps Terragni’s design is the site for the contemplation of disputed monuments and memorials—a space of the in-between and “the realm of conscious and unconscious speculation and questioning—the zone where things concrete and ideas are intermingled, taken apart and reassembled—where memory, values, and intentions collide.”2

This text was written by Mario Gooden for our upcoming publication A Section of Now. It is published here, alongside photographs by Giulia Spadafora, as part of our Catching Up With Life project.