Home is where the camera is *no clickbait*

Matthew De Santis looks at YouTube, self-broadcasting, and the home as a self-branding exercise

I first noticed a change to my digital habits in early April of 2020, a few weeks after the world had come to a standstill. In that pause I found myself, like most, drawn to spending more and more time online, specifically on YouTube obsessively watching a backlog of vlogs from a handful of rising content creators. The pandemic has seen the soft glow and endless stream of YouTube videos wash over many of our screens. This form of online engagement in the pandemic age does not require anything other than to watch and temporarily disengage from our own self-presentation online—the gaze is turned outward. What has been interesting to observe in these videos is not the willingness to broadcast oneself online—constant self-documentation and broadcasting has become the ethos of the internet—but how this lens of documentation has slowly seeped into and started to reshape, to varying degrees, the spatial reality of the home.

Like any social platform, YouTube is made up of unwritten style guides and rules, and its algorithm works to obscure the structures and forces that determine their shapes. However, a constant feature has placed the home’s interior as the YouTuber’s default setting. In part, this is out of utility—interior space allows you to control lighting, minimize background noise, and ensure a stable backdrop, but most importantly it is a space that is readily available to broadcast. It is the clandestine interiors that personalize their creators’ videos, giving an impression of intimacy as fairy lights often twinkle in the background. It is the seemingly unvarnished glimpse into their regular lives, the spaces where life literally unfolds, that helps nurture the para-social relationship between creator and audience.1 Once a place of refuge, a metaphorical backstage for life’s constant performance, the home has enthusiastically opened itself up to public viewing.

-

Para-social Relationship, a term coined by Sociologists Donald Horton and Richard Wohl in 1956, refers to the one-sided relationships or encounters between a person and media personality. Continued encounters and interactions with the media personality can create the illusion of intimacy, friendship, and identification, while the star is completely unaware of the viewer’s existence. See Donald Horton and Richard Wohl, “Mass communication and para-social interion: Observation on intimacy at a distance,” Psychiatry 19 no. 3 (1956): 215-229. ↩

In 1903, the sociologist Georg Simmel examined the emerging tension between the individual and the metropolis, and its flattening effects on the individual’s personality. While discourse around the city often frames it as a place of cultural exchange and as fostering a diversity of thought, Simmel offered an alternative view in which the city had become the seat of the exchange of money, knowledge, and rationality, and where the pursuit of these attributes bred a monoculture. In Simmel’s view, the supposed value in difference is replaced by the search for the lowest common denominator, where concern and importance are about “what is common to all” and reduced to series of transactions, the qualitive quantities of one’s selfhood equivocated to their quantitative value.1

Walter Benjamin, a contemporary of Simmel’s, reacted to the industrialization of cities by noting the growing importance of the domestic interior as a place of refuge from the publicness and commerce of the city.2 Benjamin noted that “the private individual, who in the office has to deal with reality, needs the domestic interior to sustain him in his illusions.”3 The interior, as a place to recede, begins to register traces of the self that mark surfaces, imprints which can be picked up on and read even if the person is absent. As posited by Benjamin, this personal imprint was often lost or erased within the public realm.

But it is the emergence of the internet that has shifted this set of conditions. The supposed democratizing capability to self-broadcast from one’s home while easily connecting to a larger network has eroded the privacy of the domestic interior. Under this stage of late capitalism, writer Jia Tolentino notes that “capitalism has no land left to cultivate but the self. Everything is being cannibalized—not just goods and labor, but personality and relationships and attention.”4 The home has been pulled into the public realm as the commodification of the self has repositioned the domestic interior as a fertile ground to mine, extract, and frame aspects of selfhood that can be sold—the interior has transfigured itself into a marketplace. Self-branding, lifestyle, and the material wealth they have afforded have become the design ethos of the YouTuber’s home.

In a recent article, journalist Ronda Kaysen observed that the insides of other people’s homes have long been a fixture of public curiosity: MTV’s Cribs highlighted the opulence of celebrities living in the early aughts, while cable channels like HGTV provide a steady stream of ordinary home improvement shows.5 In the same vein, YouTube has now taken this collective desire to “peer in” and spatialized it through the home studio. At its most simplistic, creating a YouTube video only requires a camera and a stable internet connection, but at its most elaborate it is composed of many parts: microphones, greenscreen, ring and box lights, sound insulation, cameras, video monitors, and more that create a video quality palatable to a viewer’s growing production standards.6

The stationary camera and its related equipment divide the room into backstage and frontstage. The former houses all the equipment to broadcast, light, and record its subject (the “YouTube Star”), while the latter becomes the setting and backdrop, holding signifiers of the subject’s selfhood. Household objects populate the domestic scenery: the shelf, desk, picture frames, tiny cactuses, couches, and so on. There is something decidedly “normal” about these spaces, as generic objects and personal effects gently intermingle in the background, suffusing an ambient selfhood throughout the video’s frame. Aesthetically, these curated interiors never veer far from the way that our own spaces may look, in part because the familiarity establishes a relationship with the viewer based on a similar likeness. The star’s personality is parsed out through the collection of their personal artifacts which only gain meaning when read together, and read in how they differ from our own.7 Applying a filmic reading to the inside of the homes on-screen reveals how they could be understood as mise-en-scène—spaces intentionally conceived with the camera’s eye in mind. Film theorists David Bordwell and Kristin Thompson note that the “design of a setting can shape how we understand story” and “dynamically enter narrative action.”8 Thinking of the home as a series of domestic sets, the staging, selection, and interaction with personal effects is not passively being documented, but actively working to shape how online personalities understand and present themselves. Like a film, the setting does not reveal a YouTuber’s personality but rather works to actively construct and shape it in order for it to be made readable and consumable online.

-

Georg Simmel, “The Metropolis and Mental Life,” in The Sociology of Georg Simmel, ed. and trans. Kurt H.Wolf (New York: The Free Press), 414. ↩

-

Walter Benjamin, “Paris, the Capital of the Nineteenth Century,” in The Arcades Project (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2002), 8. ↩

-

Benjamin, The Arcades Project, 8. ↩

-

Jia Tolentino, “The internet and I,” in Trick Mirror: Reflection on self-delusion (New York: Random House, 2019), 33. ↩

-

Ronda Kaysen, “Could Your House Be an Instagram Star,” The New York Times, 9 August 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/08/09/realestate/could-your-house-be-an-instagram-star.html. ↩

-

In 2010 YouTube launched its Partners Grants program, which gave promising young content creators the option to receive future ad revenue so they could invest in creating higher-quality videos. Continued efforts to increase the quality of video was to reposition YouTube as a destination for content. ↩

-

Jean Baudrillard touches on this idea in his book The System of Objects, where he describes the process of consumption driving a capitalist society. Objects become intimately bound up with their subjects or collector and are abstracted from their function. More so, that the thing being consumed is never the material object, but the external relationship it signifies, both read through the object itself and between the series of objects on display. See Jean Baudrillard, The System of Objects, trans. James Benedict (London: Verso, 2005). ↩

-

David Bordwell and Kristin Thompson, “The Shot: Mise-en-Scène” in Film Art: An Introduction 8th Ed. (New York: McGraw Hill, 2008), 115. ↩

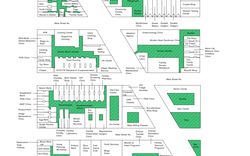

If the driver of a YouTube video’s narrative is its star, then a YouTuber’s home becomes a way to reinforce their self-brand by further spatializing it. In a recent video, popular YouTuber Mia Maples, formerly known as Ivorygirl48, gave a tour of a newly acquired house that she transformed entirely into a studio. Although an atypical use of domestic space, it reaffirms the importance of the home as the scenery for broadcasting oneself, but even more so the value it has in grounding a persona online. A clear decorative language dresses each space: suede fabrics, bright colours, bold statement walls, pottery, little succulents neatly tucked into corners, ceramic and wood shark head figurines, and photographs of her friends and family. Each room has a clear design language that footnotes Mia’s blonde and bubbly personality, while matching the sweet and lighthearted tone of her videos. This model of selfhood, determined by economic incentives, is one that doesn’t ask for these stars to be fully actualized, but instead asks them to be consistent, reducing those online to the most basic parts of their identity.1 In order for their brand to be scalable as a business, the presentation of the self can’t be complicated—and why should the way these stars show and design their “homes” be any different?

It is the sustained viewing of YouTube personalities, coupled with the repetition of the same spaces, that ascribes meaning between the star, their objects, and the spaces where they film. Self-branding recognizes and capitalizes on this series of associations, where YouTubers develop merchandise based on their subscribers’ close reading of their videos: makeup artist Jeffree Star has his own cosmetic line; Emma Chamberlain has a coffee company after starting her videos by making coffee in her kitchen; Safiya Nygaard’s website boasts a pillow with products and catchphrases associated to her (lipsticks, bats, “sh’mash that like button”). Eventually, the process of how these products are made, designed, and used becomes content that can be repurposed for their channels: an optimized system of continuous self-mining.

Its most obvious offshoot is the appearance of the unironically named “merch room,” a dedicated space to store and display a YouTuber’s merchandise sold online. Watching YouTubers James Charles or Jojo Siwa’s video tours, which have collectively amassed over 20 million views, shows that the rooms—holding merchandise sold mostly online—are modeled after different version of brick-and-mortar retail stores.2 3 Siwa’s space mimics the big box department stores like Target, Walmart, and Costco where some of her products are sold, with metal-grated shelving being overwhelmed with a variety of products. She has covered a whole wall from floor to ceiling with every version of her signature bow—which of course are for sale—as marquee lighting with Edison bulbs light up to spell out “JOJO.” Charles’ merch room echoes moments of a high-end boutique with bright lighting, bleached oak floors, monstera plants, and marble countertops, as his “Sisters Apparel” clothing line and Morphe x James Charles eyeshadow palette tidily slot into white-washed custom cabinetry.

Both rooms, however, are not storage spaces, but rather are openly displayed. These spaces, particularly for Siwa, are featured in their vlogs which closely tie persona to product. For each to ground their brand and merchandise in some sort of physicality, which mainly exists online, they draw on a concrete image and design language of retail stores. In the most literal way, traditional conceptions of commerce imprint and replicate themselves within the home, co-opting a visual language of retail to express the image of themselves online in their homes. Persona and commerce have completely coalesced.

-

Jia Tolentino, Trick Mirror, 33. ↩

-

Jojo Siwa, “JOJO SIWA MERCH ROOM TOUR!!,” YouTube Video, 10:13, November 2, 2019, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=X8mXzhBj7Xo. ↩

-

James Charles, “2020 House Tour Part 2 & 100,000 Giveaway!,” YouTube Video, 17:42, August 28, 2020, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2cZuewnE2Sw&t=251s. ↩

More than a space itself, a YouTuber’s home studio can be a flexible and portable piece of infrastructure that can effortlessly adjust to the parameters of any room, transforming interior spaces into a series of sets where the self can be displayed, performed, and constructed online. Once sacred spaces of solitude—the bathroom, the bedroom, and the closet—have become increasingly popular sites to broadcast from. YouTube video trends like “my skincare routine,” “how to pick out an outfit,” or “a day in the life of…” centre traditionally private spaces and rituals as rich sites for content production. In a recent video, Emma Chamberlain vlogs herself as she gets ready to get her nails done, moving from her bed to her bathroom to her closet, passively remarking, “I’m gonna try to be a little cute today, like not like make-up on my face cute.”1 Throughout the processes she points to the brands she is using, some sponsored, some sent to her, and others she just happens to like.

Much of the charm of YouTubers is the vocalization of a shared existential dread expressed while doing daily routine activities. The inevitable presentation of struggle, despair, and self-effacing humor works not to critique the process of selling a product, but instead to naturalize and soothe processes of consumptions and self-construction within these spaces—self-awareness works to sidestep an actual critique of the process, but acknowledges its inevitably and moves on. The products being promoted in their homes easily and quickly solve the minor problems encountered on camera. Revealing how things are produced and showing unflattering moments of oneself quelches doubts and the perception of inauthenticity. These rooms become sets for self-construction, forming an armature that supports the building of a YouTuber’s persona, and in turn their brand. Domesticity obscures the artifice of the online persona by providing access to the spaces and rituals where the self is constructed for public consumption.

Other image-based social media platforms like Pinterest or Instagram have their own aesthetic language and ideal that their users aspire to and project on. What that ideal is, is always updating itself, but while an aesthetic of candidness and graininess has made its way into Instagram, accounts which have gained notoriety through their homes and interiors still have a high and glossy production value. YouTube differentiates itself by funneling aspiration and projection through a lens of relatability. The environment has a casualness to it, like hanging out at a friend’s house, where the spaces are lived-in but tidy enough, often marked by little messes at the camera frame’s edge. Technology and culture writer Taylor Lorenz has noted that the platform was once defined by its hyper-produced and staged videos, most emblematically through stars like Jake and Logan Paul, but has seen a rise in lo-fi styles of video documenting that often involve amusingly commenting on the everyday happenings of its creator’s life.2 This change signals the audience’s growing desire for the appearance of authenticity from its online stars.3

This tonal and aesthetic shift has altered how the home is leveraged to sell something, whether the content is sponsored or not. Many channels and videos are premised around the interaction or reviewing of material goods, from make-up to tech products—half of YouTube could be understood as a consumer goods report refracted through a constructed persona. For a YouTuber to sell something requires more than just talking about and presenting products in a video, which they do, but also embedding and placing that product in their homes, which gives the sales pitch more weight. Watching videos and seeing the products that were advertised appear in subsequent videos confirms that whatever is being sold is something worth buying. The image feels less constructed, the lived-in nature of the space coupled with the material wealth that these homes connote filtering the foreignness of the product being sold. The intimacy of the home offers up a clear and realistic, but somehow better, vision that can then be replicated en masse.

A place as self-referential and reflexive as YouTube is both exhausting and generative. The logic of the platform, the way in which we convey ourselves and consume content, trains us to use and design our spaces. Underlying much of this article is a lingering question: in which ways do we mediatize the spaces we live in, whether on-screen or off? Many of us have had to contend directly with this question, particularly those privileged enough to be able to work from home, as our co-workers and bosses now peer directly into our private spaces in video calls. To some extent, either done consciously or unconsciously, we have all cleaned our surroundings, searched for better lighting, maybe even arranged our backdrops to highlight aspects of our lives. As I write this, my video background has freshly cut sunflowers neatly placed in the bottom left corner, funny, because I never really bought myself flowers until I worked from home.

What comes next is still uncertain, but the type of stardom found on YouTube has intensified a culture of idealizing the realities of others—a new iteration of celebrity made to be seen just like us, but slightly out of reach. Watching others broadcast themselves, mirroring a more refined and interesting version of our lives, convinces us that maybe even our narratives could matter too. But to matter in a place like YouTube, you have to be popular and monetizable. Perhaps we too could use our homes to broadcast our way into relevance.

-

Emma Chamberlain, “AM I BORING?,” YouTube Video, 18:49, February 21, 2021, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RFP45dpUakQ&t=15s. ↩

-

Taylor Lorenz, “Emma Chamberlain Is the Most Important Youtuber Today,” The Atlantic, 3 July 2019, https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2019/07/emma-chamberlain-and-rise-relatable-influencer/593230/. ↩

-

Lorenz, “Emma Chamberlain.” ↩

This article is published as part of our ongoing Catching Up with Life project.