A Space for a Non-Human Domestic Labourer

Anna Puigjaner on the ubiquity and commodification of non-human care work. Photographs by Alice Proujansky.

The progressive aging of Western societies and the increasing dependency that we experience as we age have fostered the gradual introduction of new care technologies to everyday life. The unbalanced demographic scenario that is being forecasted for the coming decades clearly indicates that we will imminently be facing a lack of a workforce able to provide the degree of care that these societies will require. And, in light of this ongoing social change, advanced technologies with the ability to perform non-human care work have repeatedly been envisioned and advertised as a possible solution by their creators and mainstream media. The market is already filled with a vast range of machines that manage medication doses and provide companionship, from near-invisible apparatuses to doll-like therapy robots and mechanical pets. Despite the benefits that these machines provide, their recent ubiquity raises concerns about the possible consequences they may have—not only in terms of how their commodification fosters social inequity, individualism, and isolation, but also in terms of how they will reshape programmatic needs and, therefore, how they will directly or indirectly reshape our future homes, neighbourhoods, and even the city at large.

Despite the novelty of this phenomenon, the interest in integrating science and technology in care work is not new. As an answer to the progressive incorporation of women into productive labour at the end of the nineteenth century, terms such as “domestic labour-saving devices” and “home efficiency” began to be widely used, especially following the popularization of Frederick Taylor’s theory of scientific management. Domestic machinery and technological devices began to fill houses with the intention of cutting down on the time that dwellers had to dedicate to reproductive labour. At the time, any and all work related to caring for the house and the householders was thought to have been magically reduced by means of these new technologies. Over a century later, it has become apparent that the promises made by the manufacturers of these devices were left unfulfilled and that the amount of time dedicated to care was not drastically reduced thanks to machinery. In looking back at these labouring machines, one can also observe how they are not just social artefacts but are, in fact, evidence of a particular political and economic ideology at work. Especially in the American context, after the Second World War, when the technification of the house was less about time saving and more on the privatization of the home and orienting society toward consumerism as a means of promoting mass individuation. The divisions between genders and classes were strengthened, and whatever collectivity still remained at this time was abandoned in favour of the free market: selling more goods and increasing industrial production.

Rather than discussing the necessity of or the pros and cons of this new iteration of caring technologies, we should be questioning the ideology that has allowed them to proliferate and the ways in which architecture might respond to this ideology. This consideration is especially pressing given the risk of the progressive social individualism promoted by consumer life over the course of the twentieth century being further exacerbated. Look, for instance, to the way caring robots are being disseminated in mainstream media. Nothing requires elderly care to be individually performed and supported with individual means yet all of the commercials advertising these new devices present them as being operated in the privacy of the home, signaling their designs uphold an existing ideology. As Walter Benjamin posits, when a new technology emerges it is initially applied in a way that reproduces former cultural aesthetics and social constructs. Something similar is happening here: instead of redefining the existing architectures of care and their systems, these new devices tend to mimetically replicate the existing logic that defines them.

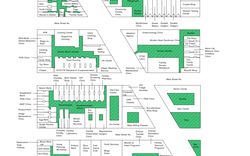

This process of domestic commodification is a call to rethink architecture as a tool for visibility and resistance. Instead of picturing these new technologies existing and being used inside homes, we could start by picturing them as part of municipal infrastructures, where non-human caretakers could provide a form of guardianship to humans. The simple action of reconceiving domestic reproductive labour as a part of the public realm would help rebalance certain existing social inequities by providing visibility, accessibility, equity, and labour regulations for care work, while also allowing collectivity to take shape outside of consumerism.

This new typology of caring could be part of the city as well as an extension of the domestic, on which it could catalyze progressive change. Thinking of domestic spaces in this way could also be an opportunity to counter the diffuse and expansive logic of late capitalism—under which the domestic has progressively become incorporated in the urban sphere—in order to allow for a redefinition of care. If the house has traditionally been the place in which unpaid and unregulated reproductive labour takes place, it might be that by rethinking its limits and its private character we might be able to find another narrative to define the domestic realm—a narrative that not only embraces non-human and technological realities but one that also addresses its economies in relation to caring practices in a manner that is more collective and socially just.

This text was written by Anna Puigjaner for our publication A Section of Now. It is published here as part of our Catching Up With Life project.