Life in the Phygital Precariat: Some newly invented terms provide an introduction to contemporary realities

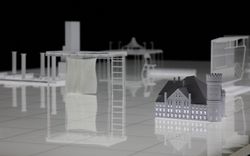

Text by Isaac Harrisson, Grace Mortlock, Lindsay Mulligan and David Neustein, Other Architects. Illustrations by Isaac Harrisson

What do you feel like eating for dinner? You’re hungry, it’s late, the fridge is bare, and you lack the energy to shop and cook. No matter, the street below is teeming with delivery people on electric bikes, ready on a click’s notice to retrieve and dispatch your chosen meal for just a small additional fee. The sheer variety of options to consider is daunting. You filter by popularity, then cost. The images that pop up give you immediate impressions of the quality of restaurant and food. Warm LED lighting tells you that the operator cares about mood. Ceramic plateware suggests an emphasis on ingredients and presentation. Glimpses of foreign script and decorative art project a sense of cultural credibility.

Collectively, these signs and symbols comprise the AirSpace of each restaurant. AirSpace, a term coined by Kyle Chayka in 2016, denotes a condition that thrives on social media platforms and proliferates through endless repetition. It exists everywhere you go, whether physically or virtually, pervading coffee shops and bars, creative offices and rental apartments, from Melbourne to Manila to Montreal. AirSpace consists of decor that is equally at home in physical space as within the limits of a two-inch Instagram square. You no doubt already recognize some of its typical features: Edison bulbs and Eames chairs, timber slats and exposed brickwork, white subway tiles, monstera fronds, and antique posters. In a single glance, AirSpace promises familiarity and comfort in advance of lived experience.

You’ve made your choice and have placed an order. But while AirSpace has informed your selection—providing reassurance that your preferred provider is clean, enjoyable, and popular—no actual restaurant will be involved in tonight’s transaction. The delivery app relays your order to a dark kitchen, a satellite operation located in a nearby industrial park. A variant of the term “ghost restaurant,” first used in a 2015 NBC New York article, dark kitchens are also known as delivery-only restaurants, virtual kitchens, shadow kitchens, commissary kitchens, and cloud kitchens. Whereas most restaurants spring up in places with high foot traffic, dark kitchens occupy blank spaces on the map. They emerge wherever there is cheap rent, nearby housing, and few competing food outlets. Such spaces are often identified, established, and owned by the delivery company and leased to the restaurateur. There is no listed address, no opening hours, no front door, no service counter. The dark kitchen exists solely to serve the delivery sector, and so is virtually invisible to the public. Your meal is prepared by kitchen staff in an unmarked converted trailer, then passed directly to the delivery worker. Thousands of similar orders are processed every evening and fulfilled by dark kitchens distributed across the city. When your package arrives within the prescribed time frame, its contents still warm and tasty, you make a mental note to add this “restaurant” to your list of go-to places.

AirSpace and dark kitchens are flip sides of the same contemporary condition: a slippery state in which things are always defined by how they appear but are rarely what they seem. Phygital is a recent marketing term for campaigns that span online and offline environments, but it can also be applied to an emerging generation that makes no practical or purposeful distinction between physical and virtual realms. To be phygital is to be equally comfortable socializing via a video game avatar or in person, to study on campus or remotely, to watch live action or e-sports for entertainment, and to pay in cash or cryptocurrency. You may already be phygital without really knowing it. Precariat is a portmanteau of the words precarious and proletariat, and is used by sociologists and economists to describe an entire social stratum of gig workers, interns, assistants, concierges, and casuals—an insecure working class tethered to involuntary part-time, short-term, and zero-hour contracts. This new and ever-growing societal subset exists on account of many inter-linked factors, including the rise of the so-called sharing economy, the hyper-monetization of urban real estate, and the deregulation of the labour market. To join the precariat is to exist within an endless and exhausting cycle: you amass debts to pay the rent, rent for proximity to work, and work to pay off your debts. For many people, especially young people, there is increasingly little alternative but to join.

The phygital precariat is where the experiential and existential overlap. Phygital space appears to offer a means of escape from the unrelenting reality of precarity, if only a provisional one. The same media and communication platforms that command hordes of unpaid workers, buy and trade our information, push products, and enslave attention can provide fleeting refuge for communities of like-minded people, or enable spontaneous outbursts of solidarity. However, before you can exercise political agency, you must first accept the standard Terms and Conditions. Indeed, whether you’re working or relaxing, awake or asleep, you can no longer opt out of your digital footprint. It’s always there, like your shadow, following you down the street. That nagging painful feeling when you’re unable to access the internet? Forget your password and find yourself locked out of your account? Run out of charge or leave your mobile device at home? That’s nomophobia, a contraction of no-mobile-phone-phobia coined during a study on mobile phone usage commissioned by the UK Post Office in 2008. Nomophobia is that all-too-familiar wave of anxiety and stress that washes over you when you’re temporarily disconnected from the network. To be separated from your mobile device is to feel vulnerable and incomplete. You probe your pockets restlessly, as if itching a phantom limb.

Some are so affected by nomophobia that they never switch off, shut down, minimize, or disengage. A burgeoning industry has emerged to soothe the fear of disconnection. Professional Twitch and TikTok streamers offer themselves up for continual, round-the-clock access. They’re there when you wake up and when you go to bed, and if you like you can watch them sleep. Recorded by cameras and microphones that capture every nocturnal stretch and snore, the sleep streamer provides a specialized type of performance. With each new subscriber, the digital alarm gets pushed back a little further, and the sleep streamer is rewarded with a few extra moments of shut eye. You can see for yourself that this isn’t “reality television:” the footage is real, live, and unedited. The streamer’s unfiltered appearance is a commodity, as is the everyday intimacy of the setting.

In the ocular-centric environment of the phygital, your personal appearance is your passport. You use facial recognition to unlock your phone, verify accounts, and authorize payments. Your face is tracked by surveillance cameras, swiped over on dating apps, and parsed by acquaintances and recruitment agencies alike. But can anyone be sure that it’s really you? Generated using artificial intelligence, the deepfake is a convincing form of illusion that can clone any subject’s appearance, voice, and facial expressions. From your everyday encounters with television and cinema, real estate and architecture, you’re already well acquainted with digital visualizations that appear inseparable from reality. Until recently, however, we lacked the technology to convincingly replicate other humans. Now, sophisticated pattern-recognition software, trained on real footage, can be used to seamlessly map one person’s guise onto another’s. Deepfakes have been used to make amusing videos and harmless pranks, to discredit politicians, falsify evidence, defraud, blackmail, and extort. At present, they’re commonly employed to create bootleg pornographic videos with lookalike celebrities. Soon they may pose a broader threat to identity and authentication. In the near future, the only safeguard against ever-more sophisticated deepfakes may be an even more advanced form of artificial intelligence that is capable of distinguishing between the synthetic and the real.

By foreshadowing the interchangeability and replicability of human identity, the deepfake is at one extreme of the phygital precariat. At the other extreme is the replacement of human capital with machines. No-collar workers are computerized agents who undertake automated tasks such as sorting parcels, filtering enquiries, identifying tumors, and scanning groceries. On one hand, no-collar workers promise to liberate us from the monotony of repetitive labour, freeing us up to be “more human.” On the other hand, that monotonous job may have been your lone means of survival. Still, on any hand, whether fleshy or robotic, anxiety surrounding the rise of the machine worker distracts us from the reality of the precariat worker class, scheduled and watched over by their no-collar counterparts, who rush to retrieve packages, answer emails, and fetch takeaway meals on command.

The dumbphone is a simple device that excludes a camera, web browsers, apps, and games. In other words, the dumbphone is simply a telephone. You might purchase a dumbphone in an attempt to cure your nomophobia. You might think of it as a retro status symbol, proof that you’re not entirely enmeshed in the phygital world. Ownership of a dumbphone signals that you’re a highly educated and conscious consumer, capable of healthy withdrawal from the attention economy. But as the Penny Farthing is to the e-bike, the dumbphone is so niche as to be insignificant. Moreover, some of these devices, which are otherwise known as feature phones, have more built-in features than others. The Punkt MP02, for example, is a minimalist black handset with tactile keys and a small, monochrome display. It can be used to tether to the internet but offers no portal of its own. While the Nokia 2720 Flip may resemble an early-2000s flip phone, its novelty appearance belies a host of functions including a video camera, WhatsApp, and Google Maps. Perhaps the most interesting thing about these various feature phones is what they tell us about the technology of the smartphone, which at this point should not really be described as a phone at all. The smartphone condenses the spaces and activities that were until recently provided by desks and typewriters, cameras and catalogues, radios and televisions, compasses and maps, wallets and rolodexes. In the absence of these physical objects, our interiors have been stripped down to little more than soft furnishings, illumination, and walls. But these walls no longer frame and delimit our sense of place. The smartphone’s screen transports us to locations all over the world, while collapsing the world into a screen.

Like the dumbphone, cottagecore is a form of self-expression motivated by nostalgia for a bygone way of life. One of many subcultures recently named and popularized through Tumblr and TikTok, it embodies a lifestyle that can be best defined as tangible, wholesome, handmade, and quaint. Cottagecore activities include baking bread and growing vegetables, sewing, weaving, and other types of craft. The pastoral aesthetic this movement evokes is at odds with its largely city-based following. More seductive than ever in these anxious, pandemic-ridden times, cottagecore is a siren call that promises the security and self-reliance of a semi-isolated rural existence. Both the dumbphone and cottagecore are symbolic forms of defiance against the aesthetics and experiences of life in the phygital precariat. Though sincere, this resistance is tokenistic. As millions of Airbnb images of rustic beams, hanging pots, clawfoot baths, and festoon lights will attest, cottagecore has already been co-opted as a form of AirSpace.

Every day, your interactions with the world around you are increasingly mediated by screens, platforms, and algorithms. The phygital precariat might generate new forms of architecture, or it might signal the point at which information technologies and architecture definitively part ways. Small, portable, and readily replaced, the devices you employ for work, leisure, and communication are largely independent of any spatial configuration, while the vast networks that underpin and connect these devices overwhelm architectural scale. Between the device and the network, however, is a precarious and ever-growing workforce, trying frantically to keep pace with the clicked commands of an online economy. To live within, or at the edge of this contemporary condition, is to recognize a deepening rift between appearance and reality, cause and effect, product and source. Will you learn to adapt to deepfakes and dark kitchens, embrace the tropes and contradictions of AirSpace and cottagecore, or overcome your nomophobia and go entirely off-grid? It’s all a lot to think about right now, and you’re due for an early start. International time shifts begin just before dawn and staff performance is strictly monitored. You ask your virtual assistant to wake you in a few hours, switch on a soothing playlist, and warmly greet your first-arriving subscribers. It’s finally time to log off, and log on. Your bedside camera and microphone will watch over you while you sleep.