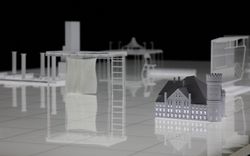

A Space for Fertility

Hilary Sample explores the connections between home and clinic

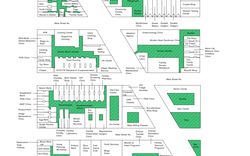

© Hilary Sample

This map reimagines the form and life of a city through all things related to infertility and fertility, from testing and treatments to the support of social life. As society still treats fertility issues as private matters, awareness occurs only through those who are actively going through or have gone through them. Treatments undertaken within institutions of hospitals and specialized clinics, or in the privacy of homes, remain private, rendering the act of treatment as secretive, possibly taboo, and misunderstood. To undo stigma and raise awareness to those who are not privileged to such services, this map is comprehensive yet incomplete. There are more services, more social connections needed to be recognized, more support needed to be given to the sensitive matters of infertility and fertility. This map highlights not only the patient but the care worker, specifically nurses, nurse practitioners, and nurse aids, who are the architects of our collective public health. It illustrates the many different aspects of fertility treatments and associated illnesses, and recognizes issues of health related to providing healthy housing.

Fertility clinics provide a multitude of services: testing and screening for early pregnancy, egg viability, hormonal levels, sperm potency, genetic diseases, coinciding for donor services, egg retrieval and storage for young women and for those who want to preserve their eggs before undergoing required treatments that would destroy them. Fertility clinics are transactional spaces—spaces in which money is exchanged for services that affect one’s health and life.

While the fertility clinic requires its patrons to potentially commit to years of effort to become pregnant, once pregnancy is “achieved,” the reproductive body frequents the clinic for eight weeks, at which point the expecting body no longer visits the clinic and returns to their obstetrician-gynecologist. Fertility clinics require short out-patient treatments, and not inpatient overnight stays. The nature of the clinic is as a space for clients with a high turnover rate, who typically require its services for only a matter of months, as opposed to the lifetimes spent with a family doctor or general practitioner, for instance. It follows that fertility clinics are less focused on creating and maintaining spaces for comfort because their aim is to have protracted relationships with their clientele rather than long-lasting ones. Emphasis is on service over comfort.

Seemingly, when it comes to fertility, the space of service in the clinic is engineered for efficiency so that it is not necessary to require its own building or even its own formal type. The word fertility is a descriptive, an adjective qualifying the noun “clinic.” Like its title, the fertility clinic exists as a hybrid form, not its own building, not identifiably separate from the set of other types that includes the office and the laboratory. The fertility clinic is frequently identifiable as such through a sign on the building’s exterior and through wayfinding on its interior. A patron may arrive through a parking lot and building lobby or through a building lobby and elevator. There is typically a check-in desk with a security guard, as security is an underlying condition through the infertile experience. Most likely there is a bathroom and water fountain in proximity to the entrance. A vending machine with candy and chocolate is part of the as found, as are few tall plants that require little water to survive. Typically, these spaces are bleak and aesthetically somewhere between a hospital operating room, laboratory, and waiting room. Whatever the building’s organization, individuals approach it with the expectation that they will be meeting others to assist them in the next steps of their healthcare—with the understanding that they are not alone.

While the idea of achieving fertility has resulted in a contemporary solution in the form of the fertility clinic, fertility is not and has never been about being alone in this singular pursuit. In fact, if fertility is looked at across cultures and throughout history, it is seldom understood as an autonomous subject and not exclusively thought of in relation to human bodies alone. There are innumerable deities dedicated to fertility, and many cultures and religions have more than one dedicated to the subject. In almost all instances, the deities responsible for fertility are also intimately linked to a rather wide range of other subjects and themes: from nature and agriculture to grains and maize, animals, love, life and death, wind and water, chocolate and rainbows, beauty and sexual power, art, healing, knowledge, and wisdom. In other words, fertility is about being connected to the elements and the world, and it is, by nature, connected to something larger and beyond any individual reproductive body. The current trend in fertility treatments, however, displaces all of these things by returning care of the reproductive body to the domestic realm, to the home, and to caring for oneself by oneself in private. As noted in a growing number of news articles, thousands suffer in silence, as society has not been openly accepting of disclosures or discussions of miscarriage and infertility. As fertility treatments increasingly tend not to require a space outside of the home for support, it returns the ill-reproductive body once again to isolation in the privacy of the home. The narrative is reconfigured by withdrawing into seclusion, and a removal from a larger social body. The question about when and where fertility should intersect the public is emerging as a crucial issue of our time.

While the clinic primarily supports the crucial care of individuals looking to have a child, it is also a representation of the respective positions of the healthy- and ill-reproductive bodies within society. The ability to receive treatments and care for infertility is already limitedly available to those who can afford the time and money necessary to alter their condition with the hopes of becoming pregnant and birthing a child. This presents a great challenge to the type as it is inclusive to some and exclusive to others. This fact makes the clinic a problematic type as it does not offer itself as a space to everyone. The question of whether there should even be a clinic dedicated to this issue is one to be considered. By propagating the clinic is the implication that only those with privilege—with time and money—are those worthy of fertility treatments, and sinisterly those worthy of reproducing? Based on how society builds and uses the fertility clinic, it seems so.

Why does there need to be a dedicated independent building or physical space outside of a hospital setting for fertility treatments? Why does the fertility clinic too often exist as a silo or seem to exist this way in the United States, despite regulatory agencies such as the Centers for Disease Control, Food and Drug Administration, and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services all in place to review? The United Kingdom offers the best available practices for regulation. And why would the only other solution be to receive these treatments at home? The answer to all these questions is, in part, because society continues to operate under outmoded adage that women “suffer in silence,” which has turned into the contemporary understanding that suffering reproductive bodies should therefore, too, suffer in silence. The absorption of the fertility clinic into another larger infrastructure would, in theory, require less maintenance costs and offer services that reflect the needs of its users, from help with mental health concerns of depression to anxiety to dealing with the physical stress of treatments. This formulation serves to make treatments available to a wider group of people, and would reinforce a sense of societal belonging among people receiving treatments. This model would also create an opportunity to support the entire development of the pregnancy, including what quickly comes after birth, when one is typically left on their own to raise a child—at least in America.

What would this setting look like? Being further absorbed into a complex, corporate, sterile setting would presumably not reduce stress or risk of illnesses such as COVID-19. That said, a retreat from the clinic to the home as the only other alternative space for care privileges few instead of many. Though it is difficult to argue against wanting to face a crisis and private matters within the comfort of one’s home, the lack of interaction with untrained professionals and with other patients is a lost opportunity for both receiving compassion and sharing knowledge. How can there be equity in care from the very beginning of life? The paradox is that when fertility treatments are undertaken within the space of an institution, they affect the domestic. Even with the move to in-home testing and monitoring of some aspects of fertility, examinations by a medical professional still need to occur so that it seems as though a complete separation of treatment from the medical institution is not fully possible. A reimagining of the fertility clinic begins by creating a new connection between mental and physical spaces, between domestic spaces and medical institutions, and between home and clinic.

This text was written by Hilary Sample for our upcoming publication A Section of Now. It is published here as part of our Catching Up With Life project.