Designing Motherhood

Michelle Millar Fisher, Juliana Rowen Barton, and Zoë Greggs speak with Alexandra Pereira-Edwards about the designs that shape motherhood

Designing Motherhood is a book, two exhibitions, an open-source design curriculum, an oral narrative portraiture project, an Instagram account, a series of public programs, and an overall collaborative effort that considers the arc of human reproduction through the lens of design.

- APE

- How do you describe the notion of designing motherhood, and what drew you to this line of investigation?

- JRB

- When I think about how we define motherhood, I think it is important to acknowledge that not all members of our team are parents, including the three of us speaking with you today. There are members of our team who have children, but our team members’ relationships to motherhood are as expansive as the project itself. To define motherhood, I’m going to quote our glossary from the Mütter Museum exhibition, because it is the best way to demonstrate that these themes of designing motherhood are not women’s issues, but human issues.

“We define motherhood as a shorthand for acts that go beyond a gender binary and beyond people who have been pregnant or given birth. It is a descriptor that can be embodied, deferred, refused, taken on as a duty or expectation, or otherwise engaged with, in all its knotty contours. Motherhood is a myriad.”

- MMF

- There are so many origin stories for this project, and each of us has a different one. Mine is grounded in labour rights around care work, coming out of being the child of a single parent who was always compromised by their status as a mother within the working world. And this was in Scotland, which does have welfare provisions that far out-rank somewhere like the US. Another catalyst for me came from working in the design world. I was at MoMA as an architecture and design curatorial assistant when I first started really thinking about this project, and I made the argument for a breast pump to join the collection. As a labour-saving device much like the KitchenAid or the Hoover, it was perfectly within design history canons, and it fit into MoMA’s fetish for machine arts principles demonstrated from their very first design exhibitions. And yet, because no decision-makers had ever lactated, it was dismissed as an object to collect or display. That led me to this project, to meeting DM project co-founder, design historian Amber Winick, and to what has become a much larger team of people.

- ZG

- It’s been almost two years now since we started working on the project. Michelle came to Maternity Care Coalition (MCC) where I work and struck up a conversation with our Vice President of Programs and Operations, Karen Pollack, about this amazing project. At the time it was very happenstance. They were like, Zoë, you’re interested in art, maybe we should put you on this? And it snowballed from there.

- MMF

- And that conversation happened because Amber and I had offered this as an exhibition proposal and book proposal to numerous colleagues and publishers, and everybody had said, this isn’t really what we publish, or it seems very niche. Collaborating with another fantastic colleague, Mexico City-based design curator Jimena Acosta, I had managed to put out a much smaller project and book on design for reproductive health. But nothing at the scale of DM. Amber and I had gone through many different possible partnerships and then we had an epiphany: we realized this project would never originate in a museum because there, it’s often lip service that is paid to community issues; to social justice, racial justice, reproductive justice. Maternity Care Coalition has been treating community outreach, doula programs, lactation advice, early childhood education, and policy and activism as a root cause of—or root requirement for—healthy cities for decades, and thinking about it as systems design. Of course they would make amazing partners! We always make it very clear that we are riding on their coattails.

- APE

- Were a lot of the objects you investigated designed by male doctors?

- MMF

- Yes and no. Some of the really interesting histories are of the designs not dreamed up by men. One of the very first objects that we looked at, the home pregnancy test, was designed by Meg Crane in 1970 while she was a packaging designer at a pharmaceutical company. Then the Egnell breast pump from 1956 was designed by Einar Egnell, a Swedish civil engineer, but he partnered with Sister Maya Kindberg who worked in the maternity hospital as a nurse. But overwhelmingly, yes, the industrial design sector has been dominated by men. One of the things that we have been really interested in doing is nuancing that, because of course teams make a lot of this material culture, so we have been thinking beyond the heroic male designer and about moments of co-creation between stakeholders and designers. The basis of the entire book is on tenets of reproductive justice, and that is a history absolutely created not by men but usually by women-identifying people of colour. And I’m fed up with writing about men in design and architecture. I took an oath some years ago that I was not going to populate more men into the canon than I needed to, only as bystanders to the history that I’m interested in writing about. There certainly are men in these histories, but we don’t really cover them unless we have to.

One example, the cesarean section curtain that we show in the Center for Architecture and Design exhibition in Philadelphia, is a nice story of design-meets-architecture that was designed by three female-identifying nurses in Virginia. The clear curtain panel maintains the sterile field, but by looking though the window, birthing people can participate in their cesarean birth and see and hold their baby immediately after.

- APE

- I want to ask more about systems design, and how law and policy shape the spaces that we inhabit and the objects that we interact with—specifically those that are implicated in motherhood.

- MMF

- I’m going to offer one concrete example from the book, and one reading. The reading I’ll start with is by Dr. Khiara Bridges, who spoke to us for a chapter in the book called #ListenToBlackWomen. During our book interview, we discussed the etymology of that hashtag and thought about the ways in which reproductive justice work has been founded on the lives, the embodied experiences, the activism, and the scholarship of women of colour. Dr. Bridges looks at the legal frameworks around pregnancy, everything from the way in which it’s categorized as a disability, to the ways that legal frameworks have divested folks—especially marginalized folks and folks of colour—of their rights around reproduction.

We also spoke to Thomas Beatie, who birthed three of his four children. He talked about his experiences as a birthing person who identifies as male, and how there was no space on the birth certificate to honour his experience as the birthing father; as somebody who does not identify with the term “mother.” So, there is a necessity for an expanded legal framework around very prosaic things like a birth certificate. He had his name written down in the space for “mother” with the birth of his first child, and actually became the first person to change that legal framework, to challenge it and have his name put down as what he is, what he identifies as, which is as the father.

- JRB

- In my mind, one of the things that makes Designing Motherhood so important is that yes, we are looking at the design of objects, but we also turn our lens toward systems and policies. What Michelle is talking about in terms of the legal systems touches on another crucial part of the discussion, which is linguistic systems and the ways in which we are extending our vocabulary to change the societal structures that impose definitions or linguistic traditions.

Also important to note is that the Associate Director of Policy at Maternity Care Coalition, Gabriella Nelson, is a city planner and is part of our curatorial team. She also thinks about those big picture, thematic, systemic design questions alongside the design of the individual objects. - ZG

- Gabriella Nelson is a powerhouse. She highlights that if the (white and often, but not exclusively, male) folks who created the system that we live in dreamt it up, we too can dream of something different; we can implement a better system, one that really nourishes and holds all of us. We are working on a narrative portraiture series titled “For the Babies” that’s going to discuss core aspects of the politics and realities of motherhood and things that directly impact families, as well as the direct service staff at MCC who do this work every day. For example, we have one episode on land and housing in which we talk about COVID and how housing policies have led to the current housing crisis. How does that impact families? How does that impact the design of a city and where people feed their families? We have huge issues with food deserts here in Philadelphia, and it’s because, in part, the design of the city is heavily segregated. It is also important to highlight that lack of access to affordable, fresh foods in certain neighborhoods (often demographically working class and PoC) is not coincidental but rather a direct result of a deeply inequitable and violent city and systems design. You can drive through and clearly see the division. We wanted to expose these topics, and dig in. We want the viewers to leave feeling knowledgeable, but also having a bit of hope, because we want people to keep their imagination. I think that’s something that the heteropatriarchal white capitalist system that we live in is working very hard to kill. Once your ability to imagine new horizons and alternatives is removed, so is your willingness to dismantle and build anew.

- APE

- It comes as no surprise that policies have very real and tangible impacts on everything from birth to family. I’m wondering what the spaces that are associated with reproduction, whether pregnancy, birth, or any other stage of the reproductive arc, reveal about these hidden frameworks?

- JRB

- The first thing that comes to mind is the “Make the Breast Pump Not Suck” hackathon, where in 2014 a team at MIT started looking at a single object, and realized that looking at the object of the breast pump was only one part, and you have to build out to understand systems and context, always. Their next hackathon in 2018 focused on paid family leave. In terms of spaces, we can also consider the Mamava lactation pod, and how a single object, or the act of feeding or breastfeeding, can have implications in many different spatial systems. For example, legally, breastfeeding must be accommodated in the workplace but so often is not adequately made space for.

- MMF

- In terms of space, too, a couple of further examples are interesting to pinpoint. On the West Coast in the 1950s, there were a series of hospitals built called “dream hospitals,” which are part of what’s become the Kaiser Permanente chain of hospitals. These hospitals came out of the Great Depression, when Dr. Sidney R. Garfield decided he wanted to help workers in Henry J. Kaiser’s industrial workplaces access affordable healthcare. After the war, Kaiser and the doctors continued their partnership to open WWII health plans and hospitals to the public.

- MMF

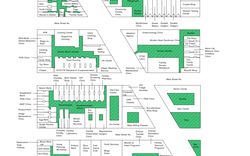

- If you imagine a fried egg, the maternity ward design had concentric circles. Right in the nucleus were the nursery and the nurses. Around the edge of that were rooms for new mothers, and then there was another concentric “circle of service” where visitors entered and exited. Connecting the nucleus of the nurses’ station and the nursery to the mother’s room were “baby drawers” which looked like a filing cabinet drawer. The nurse would look after the baby in a communal nursery, but the mom could press a button in her room, it would flick on a light, and the nurse would pass the baby through the drawer and into the room, which was meant to increase rates of breastfeeding and bonding. This was in the 1950s and 1960s, and birth was moving from the home into the hospital. That was the tipping point moment where the majority of people were delivering their children in the hospital, like 99% of people do today, whereas 99% of people delivered them at home in 1900.

- MMF

- It was also at the moment in time where people were starting to realize that the model of hospitalization and industrialization of medicine, especially as it related to maternity, was resulting in very traumatic births and postpartum periods. Sometimes you were knocked out completely, had the baby pulled out of you, woke up later, and suddenly had this strange child presented to you after coming around from an anesthetic that you probably didn’t need in the first place. Considering the baby drawer is a very interesting exercise in understanding the spatialization of a maternity ward, and in understanding the larger social structures at the time which moved midwives and other birth experts—often women of colour—from their places of expertise in favor of a white male medical model in the hospital.

- APE

- It’s shocking how quickly births moved from the home to the hospital. Is that trend still on the rise? Because home births seem to be coming back into mainstream discourse as well.

- MMF

- Home birth gathered speed again in the 1970s, when some women said they did not want to be treated on the conveyor belt of the medical model. But those were women—and almost exclusively white women—who had resources and choices. We live in the US and that’s one very specific socio-cultural location for birth. But in many cultural settings, in many countries, home birth is much more prevalent, either by choice or, conversely, where hospital access isn’t always possible.

- MMF

- The arc of human reproduction is a universal experience, in that we all got here by being born. Literally every living, breathing human shares this experience, but everybody’s birth is entirely unique. Home birth has a multivalent history, depending on location. It has also been frequently legislated against in the US because it is not profitable for the US medical system to allow people to birth at home.

- JRB

- Home births are not always cheap, though. The cost just falls onto the individual. To tie back to systemic issues, part of the reason it’s so expensive is that healthcare doesn’t necessarily cover home births, so they are often out of pocket.

- APE

- Home childbirth is often posed as something that is not a medicalized experience. It will be interesting to see if, in the future, the experience will become more accessible and less expensive, because being less medicalized means you need less infrastructure.

This makes me think of Maggie Keswick Jencks, the wife of Charles Jencks… - MMF

- Maggie’s centres! I’m Scottish, so yes.

- APE

- So you probably know that, as she was fighting cancer, she was really trying to think through the best way to offer comfort to a person who has a terminal illness, and to their families. What she argued for were very specialized spaces that are still connected with the medical aspects of a hospital, but that are designed for people who are treating cancer. In your research, will you argue that it is somehow better to have a specialized space to, say, have a baby? What are the pros and cons?

- MMF

- I spent the last weeks of my mom’s life, actually, with her in hospital, in a Maggie’s centre garden, and it was a really special, special place. I have some very fond memories of being able to be in that environment and not in a high-dependency care unit with her. To answer your question, let me tell you a little about the Designing Motherhood commitment to a new design curriculum. We worked with students last fall, and are working with students in UPenn’s design program this fall. We also worked closely with the amazing artist Ani Liu, who has created a summer program at Columbia around questions of space, design, architecture, and reproduction. It’s been so wonderful to see happen exactly what you’re describing: designers thinking about specialized places that really respond to the specific needs that people have. For example, if someone is giving birth and they lose a child during that process, the notion of not being next to somebody else—even in a closed, private room, but where you can hear the cries of other babies—is invaluable. I think a lot of student designers are all asking like, okay. If I make this room big, and spacious, and light-filled, and technologically appropriate, and individually geared to the unique needs of this demographic of user at whatever stage of reproductive health they’re at, how much is it going to cost?

This is a cost-benefit analysis that is not really shared by the taxpayer in the US; it’s extracted from the patient by a capitalist medical system. The most pressing thing that we have now come to is this change in policy, that there have to be frameworks like universal access to healthcare before we can actually start thinking productively about better spaces and better designs. But as Zoë has pointed out, too, the design doesn’t stop there—systemic racism lingers and pervades all medical systems, regardless of what they cost to the end user, and that’s the most important issue to solve. If we can do that, it is where design will finally “succeed.”

- JRB

- We’re often asked what marks success for this project. For me, the fact that these conversations are happening is not, in itself, what is successful about Designing Motherhood. Success will be measured by the continuation of the conversations. We want to make sure that this is a constant topic of conversation. It’s not going away. People are not going to stop having babies or stop preventing having babies, and the arc of human reproduction isn’t going anywhere, so it is about making sure that these stories continue to be told in order to nuance design’s response to these ever-present issues.

- APE

- There are so many different levels of inequality and injustice, and I also know that speaking about design in this seems really like the last component of the discussion. But at the same time, this is why I really appreciate your work, because through the question of design, you have been able to mobilize all the other questions. When you actually start from design, rather than starting from a kind of policy, people think okay, this is something that I can comprehend. It is interesting to use design as a way of getting people around the table.

- MMF

- I’m always interested in the imaginations of designers, but maybe not just within that rubric of speculative and critical design, as it has become known over the last fifteen or so years. I do think that one of the joys of this project has been being able to, with a really truly interdisciplinary team of people, ask questions about how we could redesign what we have, and to think about design very expansively, to treat that speculation as really life or death (which it is), and not as something that ends up as an artifact, but really does affect real people’s lives in very real ways.

- ZG

- We had one of our community advisors walk through our exhibition at the Mütter Museum in Philadelphia, and she talked about seeing herself reflected in some of the designs, and how that helped her widen the depth of knowledge that she had about her own cultural histories and the work she was doing. Something as simple as a breast pump or a speculum can really, truly represent horrific moments in history, and then other times really beautiful moments in history, where people used their imaginations to reenvision where the future could go.

As a thought partner to Designing Motherhood, Philadelphia-based organization Maternity Care Coalition envisions an equitable future, grounded in racial and social justice, where all families are healthy and connected, with all children thriving and ready to learn. MCC has been working on these tough and vital issues for the last forty years, combating the rise in maternal mortality, and fighting for families—and women in particular—to have access to culturally appropriate care.