A Space With No Trash Collection

Tei Carpenter revaluates waste

“It is not so much by the things that each day are manufactured, sold, bought that you can measure Leonia’s opulence, but rather by the things that each day are thrown out to make room for the new. So you begin to wonder if Leonia’s true passion is really, as they say, the enjoyment of new and different things, and not, instead, the joy of expelling, discarding, cleansing itself of a recurrent impurity. The fact is that street cleaners are welcomed like angels, and their task of removing the residue of yesterday’s existence is surrounded by a respectful silence, like a ritual that inspires devotion, perhaps only because once things have been cast off nobody wants to have to think about them further.”1

-

Italo Calvino, “Continuous Cities,” in Invisible Cities, trans. William Weaver (London: Vintage Books, 1974), 102. ↩

For trash collection services to cease, a radical shift in mindset and behaviour is necessary to understand that same trash in place as raw matter and raw resource1 to be redistributed, reused, and recoupled. As a counterpoint to the reliance on street cleaners in Leonia, what are the spatial and cultural implications if trash collection halts and the possibility of discard becomes obsolete? Can new collectivities form around an ontology and an economy that values everything as a resource? What is the transformative potentiality of the things around us that we live with? What are their afterlives and by-products?

As trash services stop, some municipalities roll out policies that include material usage bans of plastic bags and Styrofoam, while others focus on infrastructural innovations such as building systems with integrated pneumatic tubes to facilitate material recycling. But it is not the centralized and technological management that facilitates a cultural shift to this mode of thought, it is creative collective thinking that produces behavioural, aesthetic, and even “ethical”2 innovations that overturn individualistic capitalist habits and desires.

To sift, scavenge, salvage, repair, compost, reuse, glean, barter, recirculate: these become the new terms of living. The insatiable cycle of consumption and capital-oriented growth make way for alternative forms of labour; care; and maintenance of things, communities, and places. A reprioritization of ecology occurs, without sanitizing it, as material is kept in place and can no longer be unevenly distributed elsewhere, stored out of sight.

At the same time, the revaluation of waste introduces a culture of fixing and tinkering of those things that would otherwise be thrown away. New lives are given to broken, torn, and shattered objects in repair workshops and upcycling labs that become part gallery, part store, and part educational outlet. Sometimes the act of repair is casual, but, for some, repair increasingly becomes a refined art form, borrowing from the kintsugi technique of mending broken ceramics with powdered gold. Instead of disposing of objects when they are no longer shiny and new, breakage and repair become part of the history of those things and fissures and modifications are celebrated. Indeed, these methods and modes of living spread from ways of re-making things to ways of re-making and reusing buildings, as new architectural types arise amidst vacancies and shifting social demands. “Spolia” takes on a renewed meaning for homes and these new types, from refined kintsugi techniques of repair and binding to maximalist bricolage.

-

Following Georges Bataille’s notion of an abundance of resources rather than a scarcity of them as described in Allan Stoekl, “Orgiastic Recycling,” in Bataille’s Peak (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2007), 115–149. ↩

-

Myra J. Jird, “Waste, Landfills and an Environmental Ethics of Vulnerability,” Ethics and the Environment 18, no. 1 (Spring 2013): 115. ↩

Domesticity is no longer relegated to the single-family house or the single apartment unit. Inhabitants become part of larger metabolic cycles with their neighbours and they begin to rely on one another—one person’s compost becomes another person’s fertilizer, which helps to grow another person’s vegetables; one child’s outgrown high-tops are swapped for another child’s rainboots; one person’s old magazines transform into another person’s art canvas, and so it goes—much like an industrial ecology that translates one industry’s outputs into another industry’s inputs. A domestic ecology—a home ecology—is formed.

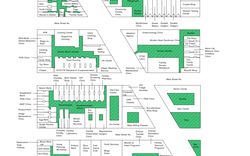

This home ecology produces an equilibrium of sorts that opens the door to a slew of new and supplementary domestic types within apartment buildings, districts, and residential neighbourhoods. Spaces previously for trash (sidewalks, bins, trash-compactor rooms, basements, garages) along with sites for consumption of the new (clothing and grocery stores, shopping malls, and the like) are reclaimed by inhabitants. Both formal and informal new economies and forms of labour are instigated as old habits of consumption and discard cease.

Individualized packaging of consumable goods, particularly food and cleaning supplies, become outdated, and, instead, people gather and shop in bulk with their neighbours and for their neighbourhoods. Bulk storage at the scales of the house, the building, and the district replace the scale of the cabinet and the pantry—the gathering of ingredients and preparation of meals becomes a shared endeavour. Types that disrupt the supply chain to create more direct relationships between suppliers and inhabitants produce a decentralization of local food distribution and recycling hubs, reducing packaging, organic waste, and diversion mishaps. Spatial formats of swap meets, barter floors, and flea markets alongside a virtual LISTSERV introduce new physical marketplaces and sites of exchange. Homes borrow and hybridize agricultural storage types at the district and domestic scales, such as the grain silo, to keep and distribute bulk goods. For the distribution of essential liquids, such as fresh drinking water and milks, local refilleries that are part gas station and part return to the wells of the town commons, open to abolish single-use containers.

In the cultivation of this attitude toward both reducing trash and trash having an intrinsic value, ways and means of living shift in a variety of ways. Some inhabitants gravitate toward an ultralight life—a streamlining and reduction of things and rituals,1 some inhabitants are liberated from the permanence of things and embrace the possibility of a life in flux with a constantly changing spatial reconfiguration and curation of things within their homes; some inhabitants double down on the commitment to their domestic spaces and objects, embracing maintenance, repair, and history. Others absorb the cultural changes in ways that are not so easily apparent, in the adoption of small shifts in daily habits and behaviours, from how they brush their teeth, to how they pour their cereal into their bowls, to what they see upon looking out of their bedroom windows.

-

Intentional Estates Agency (Tei Carpenter, Jesse LeCavalier, Dan Taeyoung, and Chris Woebken), “Some Degrowth Portfolios,” Pidgin, no. 26 (2019): 190–213. ↩

This text was written by Tei Carpenter, founder of design studio Agency—Agency, for our publication A Section of Now. It is published here as part of our Catching Up With Life project.