Skin Hunger

A conversation between artist Jamie Diamond and curator Melissa Harris on commodified intimacy and the constructed notion of family

- MH

- Where did you get the title for this project, Skin Hunger?

- JD

- This term has been mentioned in many different contexts, but typically I read about it through the lens of psychology—it is mainly used to describe the human ache for physical contact with another person. Even prior to the pandemic, loneliness was an epidemic. I think the COVID crisis just compounded a state of being that already existed. Obviously now we are all affected by aspects of this, regardless of our circumstances, and there are more severe ramifications to the current lack of physical contact and intimacy. I started this work pre-pandemic—my research began in 2015.

In many ways this project aligns with my previous bodies of work, especially when thinking about role-play and intimacy amongst strangers. In this new series, Skin Hunger, I went first to Japan because I was interested in the family rental industry; people hired to role-play specific parts within a family context. I was interested in the idea of the commodification of non-sexual intimacy. - MH

- Is paid intimacy even intimacy? Are loneliness and lack of touch the same thing?

- JD

- You could also ask: is paid sex even sex? I guess I’m programmed to think that there’s a difference between authentic intimacy and performed intimacy, but in reality it’s not so clear. Intimacy is subjective and can be performed: it might be very real for the one it’s being performed for and not for the other, or both, or neither. In all the different industries and service economies I’ve been researching, intimacy manifests itself very differently—it’s very different within the Cuddle community than, for instance, the various rental opportunities available in Japan.

Regarding loneliness being synonymous with lack of physical contact: they are not the same thing, but one is profoundly and fundamentally affected by the other whether we are conscious of it or not.

Clips from Skin Hunger (In-person cuddling sessions), Jamie Diamond (2019) © Jamie Diamond

- MH:

- Let’s backtrack for a moment for context—how does this new project fit into the trajectory of your work?

- JD:

- Early in my career, I made a series called Constructed Family Portraits where I solicited strangers—predominantly sourced from the Internet or through direct observation—to come and meet me in a rented hotel room and perform as a family. These people had no relationship with one another, yet they knew how to adapt and perform according to the specific paradigm of what a family looks like or appears to be, at least in this part of the world. I wanted to see how easy it would be to fake one of these icons, to recreate one of these idealized realities without any of the authenticity.

Ten years later I learnt about family rental agencies in Japan. I spent several weeks in Tokyo interviewing some of the founding performers in order to learn more. These roles can last any-where from a few hours to several years, and while many of the rentals serve to satisfy specific Japanese social protocols, they often serve a simpler, more personal craving for intimacy. For example, there was one older woman who performed for years as a grandmother to an obviously fictional grandson. But to her fictional grandson, she was his very real grandmother.

- MH:

- Is something like this meant to create actual intimacy, or is it simply meant to fulfill some sort of social expectation in a way that makes everybody’s life easier?

- JD:

- I think it varies. In some cases, I believe authentic intimacy and connection were experienced, while other times the service was used to fulfill an outwardly cultural or societal necessity like constructing the appearance of a whole and happy family. But there’s so much more to it than that, as I’m learning. What’s interesting to me is how the industry is growing. When I began my research in 2015, there were only a handful of rental agencies established. Now there are dozens, and there are all these other types of services you can rent out too: you can rent a middle-aged man, or hire someone to take selfies with you all around the city. You can hire a “handsome boy” to make you cry and wipe away your tears. You could hire someone to go shopping with you. It’s all become part of an active service economy.

As platonic intimacy for hire now begins to find its place in the United States, it manifests itself in different ways; adapting to domestic cultural norms, with one of the main focuses being non-sexual physical intimacy and touch. This led me to the Cuddle community: professional Cuddlers who offer paying customers the opportunity to cuddle and experience non-sexual intimacy with a stranger.

- MH:

- What is the mandate of these companies? Do they have a particular ethos?

- JD:

- The company that I find to be the most interesting is Cuddlist. Founders Madelon Guinazzo and Adam Lippin take a very intellectual and transformative approach to the importance of healthy, nurturing, consensual touch while establishing a protocol for communicating personal boundaries and consent. More importantly, they provide in-depth training to the professional Cuddlers or Touch Practitioners. The basic idea behind cuddle culture is that we live in a society where touch is restricted, yet we are hungry for touch; we are deprived of physical, non-sexual connection. In many ways, society has conditioned us to think that touch is synonymous with sex, and what they are attempting to do is separate the two. Ultimately—and I’m directly referencing Madelon here—what they are providing is a social dynamic and context that cultivates intimacy. Cuddlist and Cuddle Parties are modalities in which you pay for the conditions of authentic intimacy to arise. These conditions counter some of the social conventions and implicit norms that actually inhibit (even strangle) authentic intimacy—which is rare.

People come to the Cuddle Parties for all kinds of reasons, and in many cases it may be very important to them not to engage in touch. It is true that they are agreeing to be in a room in which touch is going to happen and they will be observing others doing that, but what they do is entirely up to them. It’s interesting how relevant all of this is, especially in regard to the #Me-Too movement and pervasive questions regarding boundaries and issues of consent. In Made-lon’s words, “We need to experience physical closeness as adults without the complications and pressures of sex.” - MH:

- In other words: the concepts of acceptable touch and of intimacy are elastic, but ground-ed in mutual consent and willingness?

- JD:

- Right, and maybe cuddling is kind of a container or rather provides a context where you can test out and actually experience your own personal boundaries, not only theoretically, not just through communicating it, but through action. It’s actually more of a workshop, a “facilitated group experience” led by a certified facilitator. A cuddle party starts with a forty-five-minute explanation on consent: what consent means; what boundaries are; how to articulate your needs and wants; and what it means to comfortably receive and to give or to deny touch. It’s done in an incredibly sophisticated and authentic way.

- MH:

- You are generally a participant in the subjects you photograph. Did you participate in cuddling?

- JD:

- Well, I really wanted to understand it and believe in it, and to do that I needed to experience it. I went to my first cuddle party and it was a really illuminating experience. I didn’t know what to expect going in. I entered an apartment, and there was an established cuddle room. On the floor there were blankets and pillows. It was a very warm and nurturing space. Communication and articulating your wants and needs is one of the first things you learn, as well as to ask before you do anything. All of this is presented as skills that are being taught. Another big thing is practicing saying “no”—something I’m not always very good at, as I want to please. Personally, I am working on saying what I want with confidence.

I think many of us are conditioned to be a certain way for different reasons, so a lot of the cuddle party is about exploring those boundaries and communication skills by learning how to ask for what we want with clarity.

- MH:

- Is there a fine line between the platonic and the sexual in this environment?

- JD:

- Yes—there can be. That’s why communication and establishing boundaries are so important.

- MH:

- So there are cuddle parties where there are many people, and also one-on-one cuddle sessions at a practitioner’s home?

- JD:

- Cuddle parties are more like a collective group experience led by a party facilitator. This person is trained to guide the group and ensure a safe and enjoyable experience. The one I attended was about fifteen people.

The one-on-one session is a very different experience. It’s just between two people: the client and the professional Cuddler or Touch Practitioner. These are trained individuals—some have backgrounds in psychology and have worked with traumatized victims of sexual abuse, and with grief. You pay them hourly and overall it is much more intimate. You typically attend a session in their home. - MH:

- When people invite you into their homes for a session, do they have a room that’s dedicated for this, or is it just a regular room in their home?

- JD:

- Usually it’s the bedroom, which is your most sacred, personal space. When you arrive, you first have a conversation—before you even touch. The rules of consent are outlined. So it’s a very clear contract and very transparent in terms of what the expectations are. I’ve worked with many Cuddlers and I am amazed by how comfortable and safe they feel, especially given that strangers are entering their home.

- MH:

- The first time you went to a cuddle party, did you bring your camera?

- JD:

- No, no. It was important to me that it was an authentic experience and that I was an active participant, rather than an observer.

- MH:

- So what happened when you did start to photograph cuddling?

- JD:

- The end of April 2019 was my first in-person physical cuddling experience. I always left the camera out of it in the beginning because I wanted to make sure that the experience was authentic, and that there was a real rapport. And now, to be honest, the camera feels very secondary. I set it up on a tripod and I set the shot up ahead of time.

- MH:

- When you photographed the cuddle party, were any of the participants reluctant?

- JD:

- So far, I have only photographed the Cuddle space—not the party itself. But for the one-on-one sessions, the Cuddlers I worked with never had any objections. I am very transparent about my project and the fact that I am an artist working within this space.

I do feel like I was able to capture the energy and experience despite the fact that, you know, there was an object—the camera—observing us. I also made video recordings, so I was recording all my experiences photographically and through video. The format of the sessions is consistent: they are about an hour long and always in the practitioners’ home. And always in bed.

What’s so interesting is that we are never really taught about non-sexual consensual touch and its implicit boundaries, and there is a real need for this. And then there are all the fine lines between, let’s say, flirtation and harassment, for example. It’s all complicated. That’s why this is so important: it is a very straightforward approach, which is all about communication and learning where those lines exist. Because right now it’s so malleable.

I was talking recently to Adam Paulman, who is a certified Cuddle Party facilitator. He described how, in our culture, we’re conditioned to think of touch and sexuality as one thing. When we get to a certain age, touch is often considered inappropriate—even when it’s totally platonic. A service like this, where you’re essentially paying for consensual touch, might in some ways help legitimize it. And there is real urgency. There is real skin hunger. So it makes sense that you would outsource this service to fulfill that human need for connection.

- MH:

- Is there an advocacy aspect? Is this about trying to help people function more authentically in their relationships? I’m just trying to wrap my head around this idea of outsourcing dynamics that feel fundamentally tied to intimate (by which I don’t necessarily mean sexual) human bonds.

- JD:

- I think there is an advocacy aspect. I know from talking extensively with Madelon that she co-founded Cuddlist in an attempt to cultivate more authentic relationships, and she does that by creating the conditions for that social dynamic to take form. Authentic connection is one of the core values taught during training. In response to your second question regarding helping people function more authentically in their own relationships, I absolutely think this is true.

Research on touch shows that it has profound impacts: it releases endorphins and oxytocin which helps reduce stress and blood pressure; enables better sleep; and increases overall happiness and well-being. What is amazing is that these health benefits don’t require you to actually know the person. You don’t necessarily need an emotional relationship—it’s about the touch itself, which has enormous healing power. The skin is the body’s largest organ.

Professional touch practitioners have told me that their clients talk very specifically about the effects touch has on them: that for weeks after the session it still fulfills them; it satisfies them and makes them happier; they’re more efficient within the workplace. It affects their relationships, friendships. There is a fundamental shift in their behavior.

There are also very real effects of being touch-deprived: it can lead to depression and anxiety and a myriad of other health issues. Even during the COVID crisis, when the practitioners were working virtually, using techniques like self-touch, eye gazing, virtual cuddling, mirror exercises—it’s not the same as physical Cuddling of course, but it was still beneficial. My first experience of a virtual session elicited such unexpected feelings. There was something very poignant and very moving about the experience of even touching an inanimate object; hearing the practitioner’s voice; hearing someone narrate the experience of touch. During eye gazing, it felt so strange to be looked at so deeply for so long through a screen. I felt a connection despite the fact that we were miles and miles apart. There was something that felt very real—maybe it was because of the one-to-one ratio, and our physical proximity to the cameras on our computers.

So many people are deprived of touch and connection, and even though this is outsourced it is satisfying that need. In some ways this may signal our future, or at least an evolution in our understanding of certain aspects of physical intimacy and personal contact. I have been reading recently about a fascinating and uncanny new AI social robot meant for children called Moxie. It’s meant to be a social companion and an educator who fulfills the need for connection and emotional learning. - MH:

- If this is our future, what does that mean in terms of the living spaces we inhabit? If we’re going to be bringing in people or robots to fill certain needs for connection, does that change the environment in which we want or need to live and work?

If so many people’s sense of connection is affirmed these days more by social media (which predates the pandemic)—I’m thinking particularly of that remarkable and oh-so-scary documentary, The Social Dilemma (USA: 2020)—than by personal interaction, what kinds of spaces will we require in the future to fulfill our needs and activities? - JD:

- For me, one of the strange parts of the individual cuddle sessions was being invited into these very, very personal spaces—yet spaces that were in some ways totally foreign to me, as I didn’t know the person at all. In spite of this, there was still some sense of familiarity in that we all understand the bedroom. We understand it as a safe place, right?

- MH:

- So why will we even have or need relationships in the future, if we can pay somebody to have sex with; pay somebody to cuddle with; rent a friend or family members. What does this say about us? I’m thinking now of Peter Handke’s book, A Moment of True Feeling. Do we still crave authenticity—one authentic moment?

- JD:

- I think that’s the big question: is authenticity reserved for the ones you are closest to, or can that authenticity exist among strangers. What do you need for something to be authentic? Can commoditized intimacy be considered genuine intimacy? Our imaginations and our needs em-brace many possible intimacies, but the sacrosanct notion that these can only be effectively serviced by those who are closest to us no longer stands.

- MH:

- Has anyone taken issue with the Cuddler community and/or practice?

- JD:

- Right before the pandemic hit, I had a studio visit with a group from a New York museum. After I presented on the work, this one older woman approached me and compared cuddling to prostitution, and was clearly very uncomfortable with the subject. I think there is still a taboo when it comes to outsourcing and paying for intimacy, albeit non-sexual. There is a lot of apprehension but I think that will change in our not too distant future.

- MH:

- What are we losing, if anything? Or am I coming from an outdated perspective of actual-ly wanting the trifecta of friendship, emotional connection, and physical connection—forget even love for the moment.

- JD:

- Maybe in the future human-machine intimacy will be normalized, and maybe it will have real benefits that enhance relationships like we’ve seen with cuddling. I often wonder: if this does become a reality, what happens then to human-to-human connection and interaction?

- MH:

- Will cuddling take on a larger role in our post-COVID world?

- JD:

- Touch is a fundamental human need, and in the current climate we are increasingly deprived of it. I think many of us are already struggling with PTSD and in some cases even agora-phobia due to COVID. The pandemic will have enormous psychological ramifications, especially amongst children.

As far as what will happen with cuddling, I hope that this makes us more cognizant of the need for consensual touch. There will need to be a COVID-conscious experience of cuddling, using the tools in place for both virtual and in-person cuddle sessions. I wonder if we will ever get to the point again where we feel safe and fully at ease being so physically close to a stranger.

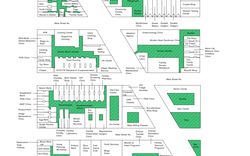

This conversation between Melissa Harris and Jamie Diamond was conducted as part of the Catching Up With Life project. Melissa Harris is photography consultant for the upcoming exhibition A Section of Now: Social Norms and Rituals as Sites for Architectural Intervention.